🕺Turn The Music Up! Vanguard, Jazz-Funk & the Secret Life of The Players Association

The Twelve Inch 198 : Turn The Music Up (Players Association)

We all have that friend, cousin, sibling or neighbour who quietly shaped our musical taste when we were young, the person who opened the door just wide enough for us to peek through and start building a world of our own.

For me, it was an older nephew. Whenever I stayed over at my aunt’s, I’d sneak into his room to see what new records had joined the collection. His taste was wonderfully eclectic. My first encounter with Bowie’s Heroes came through him, as did the fantastic Station to Station live set.

He wasn’t a disco fan exactly, but his shelves held some of the more intriguing releases of the time. That’s where I discovered Cerrone, and where I first stumbled on The Players Association. At the time I didn’t quite know what to make of it. The album had two covers, Stevie Wonder’s “I Wish” and Chic’s “Everybody Dance”, which didn’t particularly move me, and the rest felt too jazzy for my teenage brain.

This was 1979, and I was fully immersed in Eurodisco and the post–Saturday Night Fever universe. But the album’s single, “Turn the Music Up,” hooked me immediately.

The Players Association became my first brush with jazz-funk, or “fusion jazz,” as it was often called, and they weren’t alone. The Crusaders, with Randy Crawford, scored a massive hit with “Street Life” around the same time, and Herbie Hancock slipped into the Benelux charts with “Tell Everybody.”

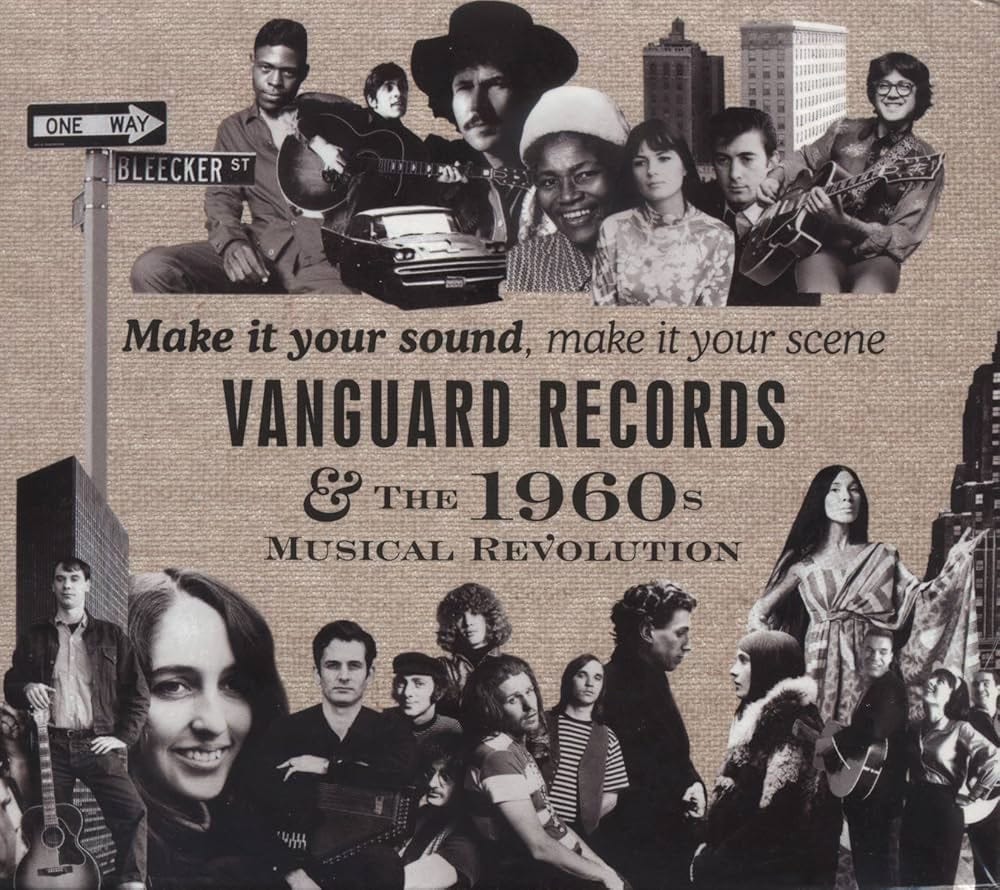

Much later I connected The Players Association to some of my favourite disco records, The Ring’s “Savage Lover” and Poussez’s “Come On and Do It”, through Vanguard Records. That sent me down the rabbit hole of the unlikely story of a label founded in the 1950s by two Jewish brothers to release blues, folk and classical music, only to pivot sharply into dance during the ’70s. The Vanguard studios would then become a hub for early electro and innovators like Arthur Baker in the early ’80s.

It’s time to shine a light on this fascinating little corner of dance history: The Players Association, and the strange, brilliant dance chapter of Vanguard Records & Studios.

Get your dancing shoes ready, and let’s dive in. 🕺🪩

👋 Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre, thanks for stopping by.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995, told one twelve-inch record at a time.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

🏛 Vanguard Records: From Folk Coffeehouses to Disco Basements

By the time disco arrived in the 1970s, Vanguard Records had already marked its 25th anniversary. Founded in 1950 by brothers Seymour and Maynard Soloman with a $10,000 loan from their father, the label had built a reputation in folk, blues and classical, music they genuinely loved, and curated with care. Quality was the brand. They dabbled in jazz from time to time, but their brief push into early rock’n’roll never sparked in the same way. And when several key folk artists, including Joan Baez, departed in the early 1970s, Vanguard’s standing in the industry began to fade.

Seymour Soloman

So when it became clear that disco wasn’t just a fad but an entire ecosystem, with DJs, clubs, mixers, 12-inch singles, distribution networks and its own charts, the Solomans pivoted. For a mid-sized indie like Vanguard, the dance market had two obvious attractions:

It bypassed traditional radio, which was expensive and tightly gatekept.

It introduced a new consumer: DJs and club kids who cared about sound quality and coveted 12-inch singles.

Maynard Soloman

But Vanguard also had something most labels didn’t…

🎙 Vanguard Studios: A Quiet Giant of the NYC Club Sound

Vanguard Studios was the in-house recording facility of Vanguard Records, born out of the label’s need for a high-quality acoustic environment. In fact as far as I understand they had two locations:

A former Masonic temple on Clermont Avenue in Brooklyn with a 35-foot ceiling, wood floors and strong natural resonance, used for Vanguard’s jazz sessions in the 1950s.

A dedicated studio on 23rd Street in Manhattan, designed to match the Soloman brothers’ pursuit of natural, high-fidelity sound. By the 1960s and 1970s, this became Vanguard’s main room for folk, rock and eventually disco projects. The space would later be rented by outside producers, remixers and indie labels during the post-disco period and into the earliest phase of electro and hip-hop (more on that later).

Because of the studio’s constant workload, Vanguard also employed its own engineers and producers. Two of them, Mark Berry and Danny Weiss, would prove central to the label’s pivot into dance music. They were soon joined by a third key figure: New York DJ Ray “Pinky” Velazquez.

🧠 The Vanguard Disco Braintrust

Mark S. Berry was one of those names you kept spotting in the liner notes if, like me, you paid attention to credits. A gifted engineer and meticulous tape editor, he understood exactly what a 12-inch needed to move a crowd. His ear leaned toward disco, Euro-disco in particular (like me 😂), and he moved in the same nightlife circuits that inspired the records.

Danny Weiss was the in-house producer, well-versed in jazz-oriented sessions. His preferences skewed toward R&B and jazz-funk. Together, Berry and Weiss formed the nucleus of Vanguard’s late-1970s dance strategy, covering the full range of what New York dancefloors demanded at the time.

For talent scouting and A&R, the Soloman brothers brought in Velazquez as a disco consultant in 1979. He later reflected on why Vanguard shifted into the market:

Billboard caught onto this in April ’78. A Vanguard insider broke down their tactic: part one was hunting for European-flavoured disco masters and acts, without ignoring domestic contenders. Part two was scanning their own pop and jazz roster for artists with “disco potential,” especially if they could cross over. Vanguard didn’t want club-only product, and they definitely weren’t about to strong-arm their jazz talent into mirror-ball territory, merely “encourage” them 😁

And it paid off. Poussez, Jazz fusion drummer’ Alphonse Mouzon’s studio vehicle, hit with “C’mon and Do It,” and The Ring found momentum with the Eurodisco-tilted “Savage Lover.”

The studio was a magnet for jazz-fusion musicians, which not only stocked Vanguard with elite session players but fed directly into this week’s subject: The Players Association.

🎺 Who Were The Players Association?

Labels loved creating their own house bands, especially when they had a stable of ace session players. Philadelphia International did it with MFSB, Salsoul with The Salsoul Orchestra, groups that not only generated hits but gave their musicians a platform. Vanguard’s Danny Weiss was looking squarely at the Philadelphia playbook when he built out the label’s disco department, so forming a house band of his own made perfect sense. Enter: The Players Association.

The project, started in 1977 by drummer/arranger Chris Hills and Weiss, became a magnet for jazz-fusion talent. Larry Coryell, Joe Farrell, David Sanborn, James Mtume, Mike Mandel and others passed through its sessions. The band wrote a bit of original material, but the emphasis was on reimagining contemporary soul, funk and disco tracks. The sound was disco-funk with a heavy jazz-fusion accent, bright, rhythmic, and unmistakably musician-led.

They scored their first club hit with a sleek cover of Diana Ross’s “Love Hangover” in ’77. The wider breakthrough arrived in ’79, when “Turn the Music Up” crossed over into the European pop charts.

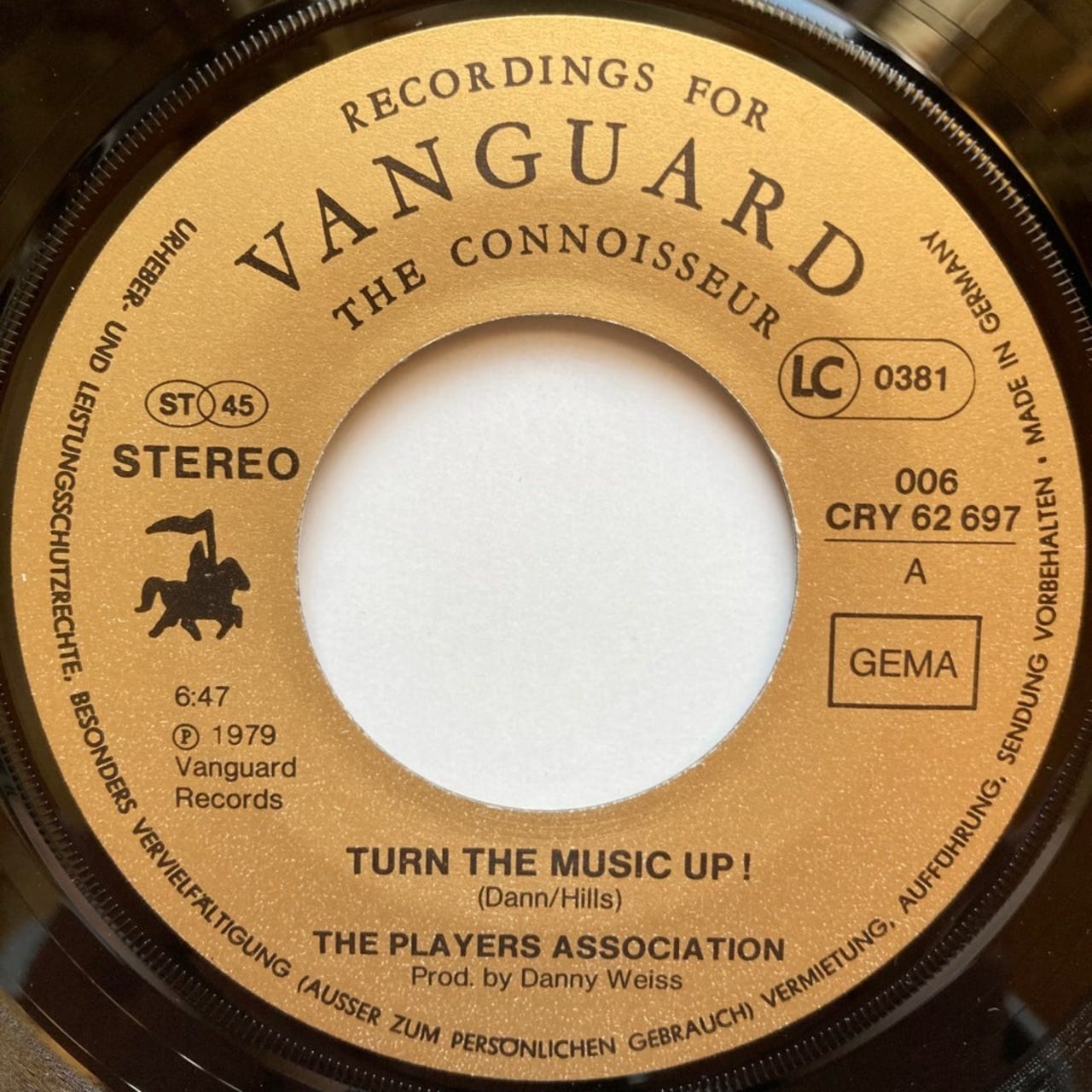

🕺 Enter “Turn The Music Up” (1979)

Released just as disco hit its commercial peak, “Turn the Music Up” was arguably the clearest expression of the Mark S. Berry / Danny Weiss collaboration. The track rides on a jazz-funk chassis with an unmistakable R&B foundation, yet the synth figures give it the aerodynamic sheen needed to sit comfortably in a Eurodisco set. In a city where jazz, disco, Latin and R&B musicians shared rehearsal rooms, the hybrid made perfect sense. It was conceived as the group’s flagship original cut, rather than another jazz-funk-to-disco cover.

Commercially, The Players Association saw modest action on the U.S. Billboard dance charts and steady club play stateside. But the real twist came across the Atlantic: the record hit far harder in the UK. Across the Benelux it reached the top-20; in Britain it went one better and broke into the top-10.

🇬🇧 Jazz-Funk, Brit-Funk & Why Britain Took Notes

As the U.S. edged toward boogie, post-disco and electro, the UK began cultivating its own jazz-funk ecosystem, driven by DJs like Greg Edwards, Robbie Vincent and Chris Hill, and by a new generation of British Caribbean, African and South Asian musicians who reworked U.S. imports into something distinctly British.

Groups such as Light of the World, Central Line, Incognito, Beggar & Co and Hi-Tension didn’t arrive out of thin air. They were absorbing The Players Association, Kleeer, Cameo, Tom Browne, Lonnie Liston Smith, Norman Connors and Roy Ayers Ubiquity, and then refracting those influences through London and the Midlands’ club circuits.

I covered the emergence of Brit-Funk in the episode on Idris Muhammad’s “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”, a record that underperformed in America but found a far more receptive audience in the UK. That was 1977, it narrowly missed the Top 40. Two years later, The Players Association landed in exceptionally fertile soil. This is ultimately why Britain embraced the band (and “Turn the Music Up”) so strongly. In the UK, the disco-funk-jazz overlap fed directly into the late-’70s/early-’80s jazz-funk and Brit-Funk club scenes, which in turn seeded jazz-dance and, later, acid jazz.

📀 Vanguard’s Disco Arc & The Backlash

The 1979 disco backlash hit everyone, Vanguard included, but unlike TK or Casablanca, it didn’t sink the label. Vanguard kept operating into the ’80s, thanks in part to the studio, to its New York footing, and to a small cluster of talent that helped the label pivot rather than collapse.

One of the most important additions in 1979 was Bobby Orlando. He began producing for Vanguard on projects such as Free Expression, and signed Roni Griffith, who scored big with “Desire” and “The Best Part of Breaking Up.” Bobby would eventually launch his own operation (a story for another episode), but in the early phase many of his productions flowed through Vanguard.

Mark S. Berry, meanwhile, engineered some of Arthur Baker’s early electro sides, including Afrika Bambaataa’s “Looking for the Perfect Beat”, and Vanguard signed its own successful electro-funk act, Twilight 22. And the label still had hits left in it: Alisha’s “Baby Talk” delivered one of Vanguard’s last major dance successes in 1985.

By the mid-’80s, however, the studio’s dance era was winding down. Berry departed in 1987, and the label was sold to the Lawrence Welk Group; the original Vanguard studio operation was gradually phased out as a distinct in-house facility.

🎛 So Why Does It Matter?

Vanguard Records, and its in-house vehicle, The Players Association, showed how disco opened doors for independent labels and entrepreneurial producers. It also underscored just how far talent and craft could take a small operation. Disco was never just a hit-and-run hustle; at its best it depended on vision. What The Players Association made was sophisticated disco: soul, funk and jazz refracted through tight arrangements and club-ready production. That’s why “Turn the Music Up” still works today. For a moment, a folk/classical/jazz label like Vanguard became a conduit through which New York’s studio jazz musicians entered the wider disco and club-jazz continuum.

Their story also reminds us that New York remained the engine of disco and its immediate aftermath. When the backlash came, many non-New York operations folded, Casablanca and TK among the casualties, but the city’s independents endured: Salsoul, West End, Prelude and, yes, Vanguard.

While neither The Players Association nor Vanguard’s late-’70s catalogue has been canonized in jazz histories the way Miles Davis or Herbie Hancock have, in dance-music terms they were crucial. They helped move jazz-funk vocabulary into mainstream disco culture, seeding later club-jazz, rare groove and the broader idea of “sophisticated” dancefloor music.

And they were early. In their wake came a wave of American jazz-funk and fusion artists crossing into the pop charts. In the back half of 1979, Herbie Hancock landed with “Tell Everybody” and The Crusaders (with Randy Crawford) scored big with “Street Life.” The momentum carried into the early ’80s with George Benson, Grover Washington Jr., Tom Browne’s “Funkin’ for Jamaica” and Al Jarreau’s “Roof Garden.”

The Players Association were not the whole story, but they were a hinge in it. A brief moment where New York’s jazz musicians, disco’s studio culture and the ambitions of an independent label aligned, and in doing so left the dancefloor a little more musical, and a little more sophisticated, than they found it.

📣 Your Turn: Were You There When They Turned The Music Up?

Did you dance to this in a club? Own the 12-inch? Discover it later on a compilation or reissue?

Did you get into jazz-funk through disco, or disco through jazz-funk?

I’d love to hear your memories, stories, and favorite tracks from the era, especially if you were part of the UK jazz-funk or early Brit-funk scenes.

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

The TOTP problem: what do you do when a studio band suddenly has a hit? In the UK, Top of the Pops solved it by featuring the dance troupe Legs & Co.

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Youtube. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

This week’s mix dives deep into R’n’B-rooted American disco and jazz-funk, with The Players Association’s Turn The Music Up at the center of the story. You’ll also hear heavyweights like Herbie Hancock with the sparkling You Bet Your Love.

On the jazz-funk/fusion side, I’ve pulled in Goody Goody (Vincent Montana Jr.’s fusion project for Atlantic), George Benson, and Alfredo De La Fe, balanced by big dancefloor favorites of the era such as Gene Chandler’s Get Down and Sister Sledge’s unstoppable He’s The Greatest Dancer.

There are also some deeper cuts in the mix: the rare Tom Moulton mix of Stephanie Mills’ Put Your Body In It and John Morales’ elegant rework of Jean Carn’s Was That All It Was.

Enjoy the ride! 🎶

Next week, we jump into the early-eighties electro era with a record that helped set the tone for the rest of the decade.

Yes, I was there while all this happened. I personally played with, hung with, dined with, danced with, drank, drugged and sex’d with in the dance club scene. Brooklyn life was portrayed reasonably accurate in Saturday Night Fever movie. Players Association, Poussez, etc., etc. were all heavy rotation and among the first that I noticed who had the BPM listed on the record. As a DJ who had to use my wristwatch then write the BPM on the jacket, I especially appreciated this. Naturally, I didn’t trust it completely, so I checked it with a wristwatch 😂.

While you have a face for radio, a voice for horror movies, your format of narrated journalism is fantastic. I love your show, the format AND, of course, the music. Really spectacular!! I look forward to all the future pieces. I ❤️ NY LGA2IBZ