🇳🇴 The Spy Who Missed the Beat: A-ha, John Barry & the Battle for a Bond Anthem

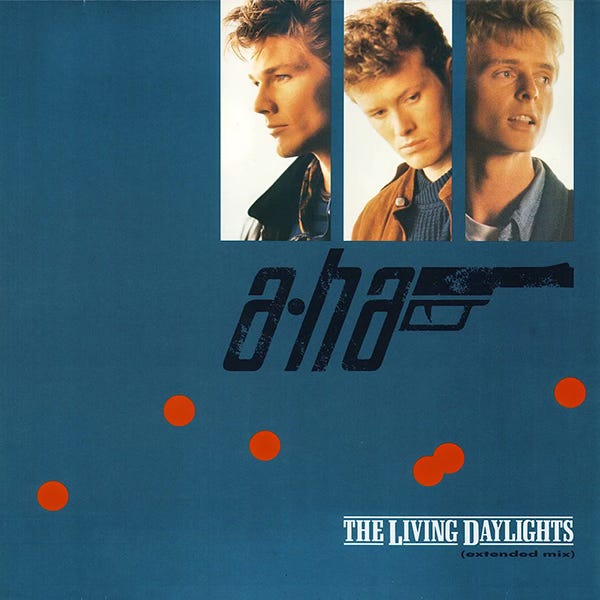

The Twelve Inch 197 : The Living Daylights (A-ha)

Let’s start with a bit of housekeeping… again. After premiering the read-out-loud version of The Twelve Inch last week, I already have to announce that the read out loud version of this episode (and possibly the next) will be delayed.

In all honesty, I had such a good time recording the first one that I was genuinely excited to tackle the next. Sadly, my microphone did not share my enthusiasm. No matter how I pleaded, bargained, or even begged him to join me for round two, he refused to cooperate. (I assume it’s a “he”, partly because of the shape, and partly because.. well you know “a dirty mind is a terrible thing to waste.” 😂)

To make matters worse, he must have sensed that his replacement was already on the way. And here’s the catch: the new mic won’t arrive for a few more days. He knew he had leverage and used it.

So, no read-out-loud editions yet. But they will arrive, loud and clear, once the new microphone settles in.