💋 “In Private”: How Dusty Springfield Found Herself Again (with a Little Help from the Pet Shop Boys)

The Twelve Inch 189 In Private (Dusty Springfield)

I didn’t really know Dusty Springfield until she turned up on the Pet Shop Boys’ hit “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” I recognised her name, of course, it often came up on the sixties music radio show I loved to listen to every Friday morning in the eighties, but that was about it.

It was only through that Pet Shop Boys track, and her brief return to the charts that followed, that I began exploring her catalogue. And what a discovery that was: a treasure trove of perfectly crafted pop and soul. Together with Dionne Warwick, she’s one of the two singers who truly defined the Bacharach & David songbook. I even have a playlist called “Dusty & Dionne” on my phone, their greatest sixties recordings side by side. Some Burt Bacharach songs appear twice: once sung by Dusty, once by Dionne. Choosing between them? Impossible.

Dusty Springfield’s place in British music can hardly be overstated. She was a remarkable vocalist with impeccable taste and an obsession for quality, qualities that make her records still sound timeless today. Her deep connection to Black American music gave her an authenticity that few British artists ever achieved. Cliff Richard once (controversially) called her “the White Negress,” a clumsy label but one that pointed to her fluency in soul and R&B idioms. Her 1964 debut solo album included no fewer than seven covers of songs first recorded by African American artists.

But Dusty’s affinity wasn’t just musical, she genuinely felt more at home in the African American community. She was instrumental in bringing Motown to a wider UK audience, championing the now-legendary 1965 “Ready Steady Go! Motown Special,” which helped break many Detroit acts in Britain.

Then, after a run of hits on both sides of the Atlantic, it all stopped. By the end of the sixties, Dusty faded from view, only to reappear in 1987 on that Pet Shop Boys duet. That revival led to another collaboration, “In Private,” in 1990, the track we’ll explore in this week’s newsletter.

So what happened to Dusty in between? Did she ever try to reclaim her sixties stardom? And why didn’t it work out the way it should have?

Those were the questions that kept circling in my head as I fell in love with her voice and her catalogue. Let’s dig into the story together, shall we?

👋 Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre, thanks for stopping by.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995, told one twelve-inch record at a time.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

🌟 Who Was Dusty Springfield?

If you’re not British, this might not sound like such a strange question. Dusty Springfield did enjoy some success in continental Europe during the sixties, but her real fame, the kind that put her permanently in the upper reaches of the charts, was mostly confined to her homeland and the US.

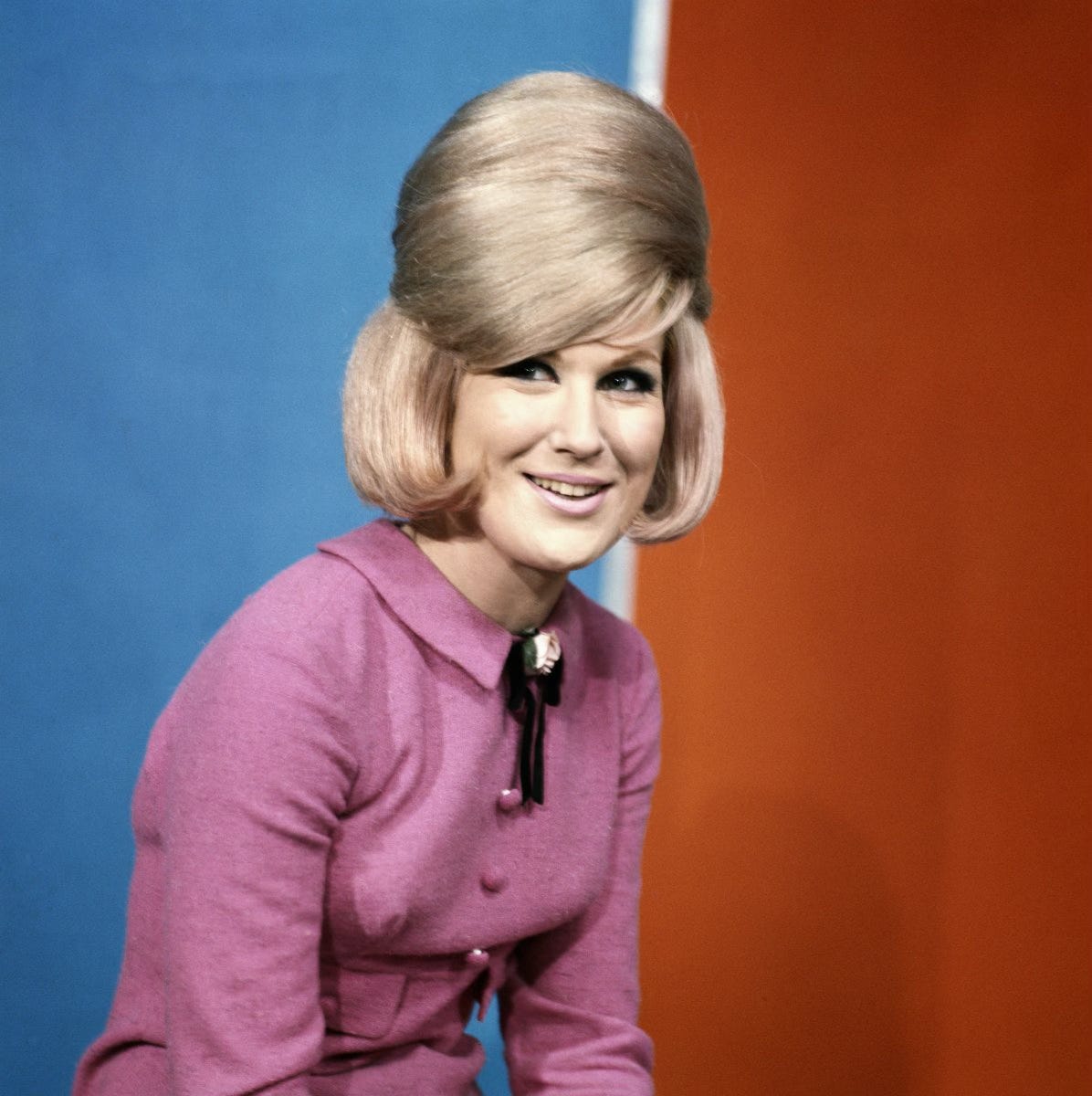

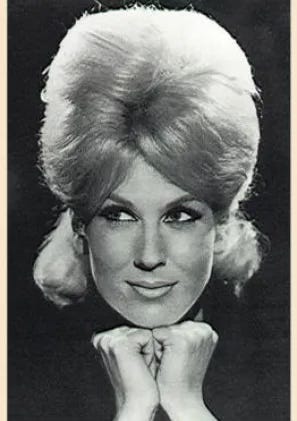

The famous “beehive”with room for a lot of bees 😂

Born Mary Isobel Catherine Bernadette O’Brien in 1939 in West Hampstead, Dusty Springfield grew up in a household full of contradictions. Her parents were of Irish Catholic descent and unusually close to the local priest, who seemed to live semi-permanently in their home. “It was like living in Father Ted,” Dusty would later say.

There was also something distinctly offbeat about everyday life in the O’Brien household. Mealtimes were tense, chaotic affairs, “pass the potatoes” could result in the entire dish being hurled to the floor. Vegetables would go flying across the table; food-throwing was practically a family sport. Dusty inherited that habit too.

Outwardly, the O’Briens might have seemed quietly respectable, but happiness was in short supply. Her father, an accountant obsessed with tidy columns and balanced figures, clashed with a mother who longed for more colour and excitement but rarely said so aloud. Together, they raised two children who grew up deeply suspicious of marriage and never entirely at ease with each other as adults. Dusty, in particular, lacked any real sense of parental affection. Her brother was the golden boy, the “blue-eyed” favourite, excelling at school and destined for success.

The only time Dusty felt close to her mother was at the cinema, watching matinee musicals. In those darkened theatres, she could escape into Technicolor fantasies, imagining herself singing and tap-dancing with Fred Astaire, wearing swirling gowns and long blonde hair.

Those less-than-ideal beginnings left their mark. They help explain her lifelong struggles with self-doubt, her bouts of erratic behaviour, and her tendency to “hide” behind the thick makeup and towering beehive wigs that became her trademark in the sixties.

Her professional path began almost by chance. Responding to a newspaper ad, she joined a girl group called The Lana Sisters. A few years later, when her brother Tom formed a folk duo and invited her to join, she jumped at the chance. The trio became The Springfields, and made history as the first British group to crack the US Top 20, years before the British Invasion.

It was with The Springfields that Mary O’Brien became Dusty Springfield. In 1963, she launched her solo career with “I Only Want to Be with You”, the very first song ever performed on Top of the Pops, and a hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

From the outset, Dusty’s compass pointed firmly westward. Her inspiration was American. She possessed something few white British singers of the time could claim: genuine soul. She studied American R&B like scripture, haunting London’s Marquee Club, hunting down Motown imports, and even visiting Harlem record stores to learn what made singers like Aretha Franklin and Dionne Warwick tick.

🎙️ The Sixties: The Rise of a Perfectionist

From 1964 to 1969, Dusty Springfield practically lived in the studio. “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself,” “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” “The Look of Love”, each of these records was crafted with obsessive care, arranged and produced to perfection.

But that pursuit of perfection came at a price. Dusty was famous, or infamous, for her demands in the studio. She would insist on endless takes, chasing a sound only she seemed to hear. Sometimes she’d sing from inside a stairwell to capture just the right echo. Engineers joked that Dusty could hear frequencies even dogs couldn’t.

Still, as the sixties moved on, the sound of soul was shifting, from polished elegance to raw funk and trippy psychedelia. British pop, too, was turning toward guitars, distortion, and experimentation. By the decade’s end, Dusty’s lush orchestrations suddenly felt like they belonged to another era.

🌫️ The Seventies: Lost in America

Dusty had always felt a deep connection with America. So when her contract with Philips, her original label, came to an end, she didn’t renew. Instead, she followed her instincts and signed with Atlantic Records, home to one of her greatest idols, Aretha Franklin.

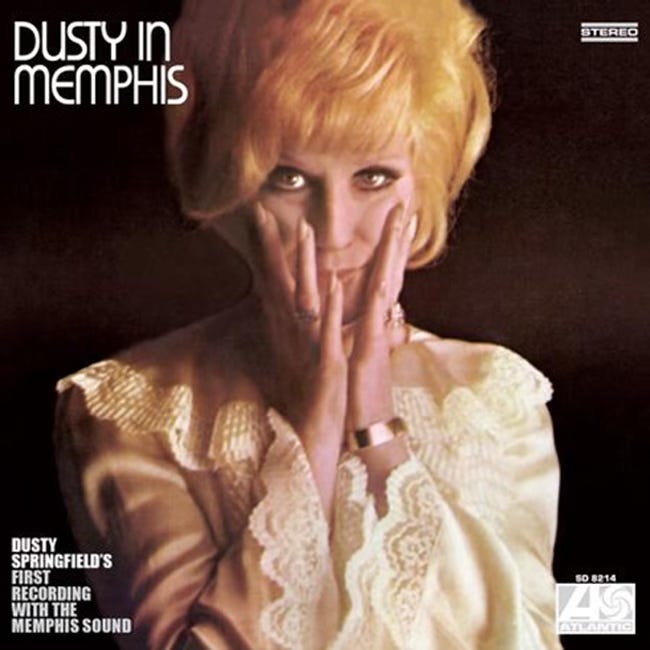

Her first Atlantic album, Dusty in Memphis, is now regarded as her masterpiece, and one of the defining albums of the late sixties. But at the time, it was a commercial disappointment. In the U.S., it sold barely 100,000 copies, and it didn’t perform much better in the UK or across Europe. The one bright spot was the single “Son of a Preacher Man”, a song originally offered to Aretha (who turned it down), which became Dusty’s last major Top 10 hit on both sides of the Atlantic.

Dusty’s move to the U.S. in 1970 was meant to be a fresh start, her reinvention. Instead, it turned into a kind of exile.

She stayed with Atlantic to record a follow-up album at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, the same hallowed space where Gamble & Huff were shaping the sound of Philly Soul. But while artists like Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes and The O’Jays were soaring, Dusty’s A Brand New Me quietly slipped through the cracks.

🥃 Addiction, Perfectionism, and the Myth of the “Difficult Artist”

For the first time, Dusty’s career had truly stalled, and at the same time, the cracks in her fragile psyche began to widen. By the late sixties, she had started to secretly self-harm, taking a razor to her arms. She would later joke about the scars, saying she’d never liked short sleeves anyway. But behind that bright, witty mask, much darker struggles were taking shape.

After her Atlantic years, Dusty settled in Los Angeles. She tried to rebuild, signing to various labels, chasing the idea of a comeback, but nothing seemed to work. By the mid-seventies, Dusty Springfield had all but disappeared from the public eye.

One of those failed come-backs: the single of a 1982 album on… Casablanca (I know we can’t seem to escape the record label)

The very trait that had made her sixties records timeless, her perfectionism, became a curse when the industry moved on. Few labels wanted to take a chance on a strong-willed artist who demanded long studio hours and wasn’t aligned with the latest trends. The result was a downward spiral.

Dusty slipped into depression and addiction, using alcohol and drugs to numb the pain. The self-harm continued, and she moved in and out of treatment centres. The money she’d earned during her glory years drained away, and worst of all, the addictions began to take their toll on her most precious gift, her voice.

🌈 Coming Out, Coming Home

Dusty was lesbian, though coming out was never easy for her. She first hinted at her sexuality in a 1974 interview with Ray Connolly for the Evening Standard. In it, she spoke candidly, and with characteristic humour, about attraction: she wasn’t bothered by girls running after her, she said, and was ““perfectly as capable of being swayed by a girl as by a boy.”

Even before that, Dusty had lived with female partners, but in an era when the music industry believed that coming out as gay could end a career, she kept her private life largely hidden. After the interview, she reportedly laughed and told the journalist, “Do you realise, that what I’ve just told you could put the final seal to my doom. I don’t know, though, I might attract a whole new audience.”

Her lifelong self-doubt, shaped by a troubled childhood and a deep mistrust of relationships, made intimacy difficult. Combined with addiction, it was a volatile mix, not exactly a foundation for stability or lasting love.

Dusty never made a grand “coming out” statement. In her official biography, she admitted to fearing being labelled a “big butch lady.” She disliked stereotypes and never wanted her identity to be defined by them, perhaps one reason why she remains such an enduring queer icon. She wasn’t political about her sexuality; she simply was.

When she later sang “In Private,” it felt like the sound of a woman quietly acknowledging her truth, even if the words were wrapped in ambiguity.

🪩 The Eighties: The Pet Shop Boys Connection

And it was precisely that queer connection that would spark Dusty’s comeback. When the Pet Shop Boys were looking for a female vocalist for a song on their second album, “What Have I Done to Deserve This?”, someone in their management office suggested Dusty Springfield, knowing she was one of Neil Tennant’s favourite singers.

Although Dusty’s career had completely stalled by then, Tennant later recalled:

Even so, when they first approached her, Dusty said no. It was only when they asked a second time, and because she liked “West End Girls”, that she finally agreed.

The label wasn’t thrilled. To Parlophone, she was a has-been, a “difficult artist” with no current fanbase. But the session proved them spectacularly wrong.

The first take was shaky, she hadn’t been inside a proper studio for years, yet once the red light came on, Dusty transformed. Every line carried drama, vulnerability, and power. The result was electric.

“What Have I Done to Deserve This?” shot to #2 on both sides of the Atlantic. After nearly two decades in the shadows, Dusty Springfield was back.

💿 “In Private”: Secrets on the Dancefloor

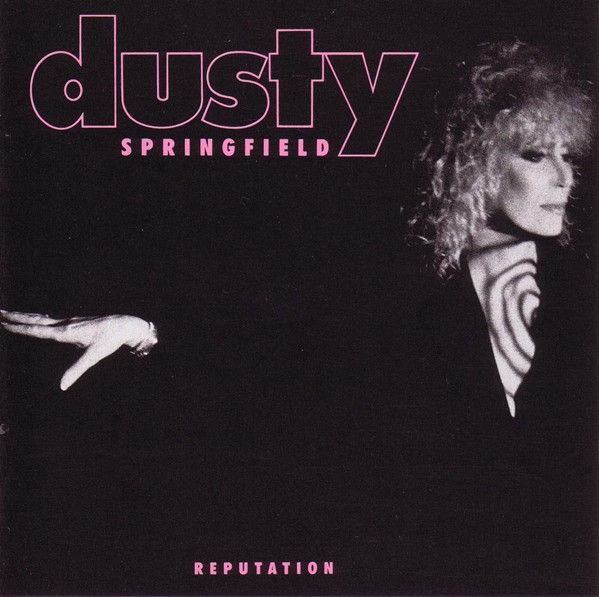

You could almost take the title “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” literally, because it took nearly three years to go from that comeback hit to “In Private” and the Reputation album.

If the Pet Shop Boys collaboration had proven to Parlophone (and the world) that Dusty Springfield could still deliver hits, it wasn’t enough to make the label move quickly. The Pet Shop Boys wanted to produce a full album for her but knew it wouldn’t be easy to get approval.

The real breakthrough came when they were asked to work on the soundtrack for Scandal, the 1989 film about the Profumo affair. Dusty was the obvious choice to sing the theme song, “Nothing Has Been Proved.” The single became another hit, and an important step in rebuilding Parlophone’s confidence in her.

Still, the label hesitated. It wasn’t until “In Private” became a major European success that they finally gave the green light for a full album. As Dusty later explained:

The Pet Shop Boys didn’t end up producing the entire album, some tracks were handled by Dan Hartman, but the overall sound was sharp, contemporary, and confident.

When she was later asked if she was happy with Reputation, Dusty replied:

“In Private” had actually been written for the Scandal soundtrack, but the film company thought it sounded too modern. Instead, it became Dusty’s final big hit, reaching #14 in the UK, #2 in Belgium, and the Top 10 across much of Europe.

The 12-inch remix by Shep Pettibone (fresh from Madonna’s “Vogue”) turned “In Private” into a full-on club stormer, giving gay dancefloors from London to Brussels their Dusty moment. Curiously, though, the song never charted in the U.S., not even on the dance charts.

📀 The Success—and the Silence After

“In Private” cemented Dusty’s comeback. But behind the renewed glamour, she was still struggling, with her health, her addictions, and the same insecurities that had haunted her for decades. While the recording of “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” had gone smoothly, the sessions that followed were far more difficult.

Part of the tension came from differing expectations. Parlophone clearly wanted more “In Privates”, sleek, danceable pop records, but Dusty wasn’t interested in repeating herself. As she put it:

So while Parlophone may have hoped for a follow-up album, it never materialised, and eventually, she was dropped.

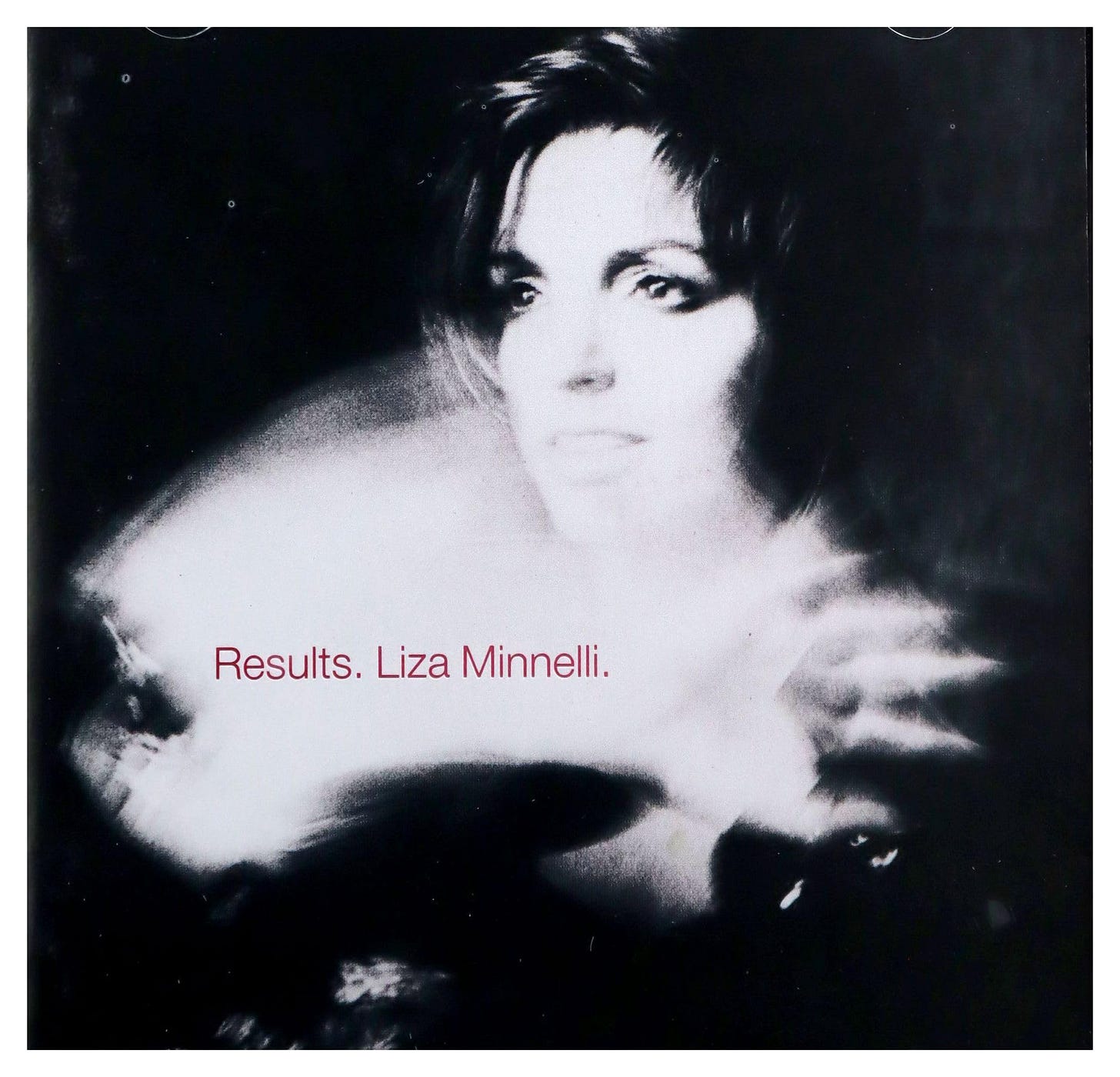

Looking back, it feels like a missed opportunity. The Pet Shop Boys could have done for Dusty what they’d done just a year earlier for Liza Minnelli, reinventing her with their dazzling, contemporary production on Results. But Tennant and Lowe were wary. Dusty’s perfectionism, driven by self-doubt and the nagging feeling that she was, in her own words, “a fraud”, made recording exhausting.

As Neil Tennant later recalled in the Pet Shop Boys’ 1990 tour diary Literally:

“Doing a whole album with Dusty would probably give you a nervous breakdown. She recorded Nothing Has Been Proved one syllable at a time. It took two days.”

🇬🇧 Legacy: The Soul of British Pop

Dusty Springfield’s importance to British music can’t be overstated. She bridged American soul and European pop, and while she wasn’t part of the disco explosion that followed, she was crucial in bringing Motown to the UK, and, by extension, to the rest of Europe.

And then there’s Dusty in Memphis, her masterpiece. It’s hard to believe it flopped on release. If you listen to just one of her albums, make it that one.

She wasn’t part of the disco explosion but Dusty did try disco in 1979. A modest hit on the US dancefloors

But Dusty truly shone in the Bacharach & David songbook. A great singer elevates a song, and her sixties recordings prove it again and again.

As Neil Tennant once said:

🕯️ The Final Verse

In the mid-1990s, Dusty was diagnosed with breast cancer. She passed away in March 1999, aged just 59, only days before she was due to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The years of struggle and self-abuse from the seventies and early eighties had surely taken their toll.

Her final television appearance was a fitting one, performing “Where’s a Woman to Go” with Jools Holland on Later…, joined by Alison Moyet and Sinéad O’Connor on backing vocals. A poignant, beautiful farewell.

💬 Your Turn

Do you remember hearing “In Private” for the first time?

Did you rediscover Dusty through the Pet Shop Boys—or through those velvet-voiced sixties singles?

Share your memories, your vinyl finds, or your favorite Dusty tracks in the comments below.

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Soundcloud. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

We open this week’s soundtrack with some pure pop-house energy. I start with the commercial twelve-inch of Dusty Springfield’s “In Private”, before handing things over to the Shep Pettibone club remix. By the time we hit the break, it’s Shep’s version that takes over — and it becomes the perfect launchpad into Jimmy Somerville’s “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real).”

From there, we glide through Lisa Stansfield and one of Grace Jones’ underrated gems, “Amado Mio,” leading into Just Strauss’ excellent remix of Belinda Carlisle’s “Summer Rain” and Information Society’s bold take on the ABBA classic “Lay All Your Love On Me.”

One of the joys of putting these mixes together is slipping in personal favorites — like Akasa’s “One Night In My Life,”a track that somehow never became the hit it deserved to be back in 1990.

And if you’re not already on your feet by then, the finale will do the trick — a burst of pure Eurodance energy featuring Technotronic, Culture Beat, Chimo Bayo, and New Order.

Enjoy! 🎶

Next week, I’ll be diving into one of the finest dance tracks of 1977: “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This.” You’ve probably heard it, maybe even through a sample, but how much do you really know about the man behind it, Idris Muhammad?

I’ll admit, Dusty Springfield was someone I’d only known through passing references and that unforgettable moment on What Have I Done to Deserve This? — but this essay completely changed that. The depth of storytelling, the honesty about her inner conflicts, and the way it connects her voice to the cultural pulse of every decade she touched made me realize how much I’d overlooked.

I’m now genuinely inclined to revisit her catalogue, starting with Dusty in Memphis and working forward to In Private. The piece illuminated her as more than a pop icon — a complex, wounded perfectionist who poured every bit of her searching soul into the microphone. It’s rare for an essay to send you straight to the turntable, but this one did exactly that.

Finally got around to reading this as promised! And it was wonderful. You’ve given a somewhat forgotten queer icon (at least in the U.S.) a moving, in-depth tribute, and as a big fan of classic Pet Shop Boys, it was great to see them weaved in here too 💜