🌈🎛️ Homosapien : Pete Shelley, Martin Rushent, and the Song That Changed Everything

The Twelve Inch 201 : Homosapien (Pete Shelley) Part 2

Welcome to part two of the story of Pete Shelley, Martin Rushent and the birth of synth-pop as we know it.

In part one, I set the scene: who Pete Shelley was, who Martin Rushent was, and how the two began working together. What started as early demo sessions for a fourth Buzzcocks album gradually shifted into something else entirely, Pete’s first solo record. Along the way, they stumbled onto a new electronic sound that would define the early eighties.

The twist? That sound would become hugely successful, just not for Pete Shelley, but for The Human League.

At the centre of this week’s episode is “Homosapien”, the track often blamed (or credited) for how things unfolded. But was that really the whole story?

That’s what we’ll unravel in part two.

👋 Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre, thanks for stopping by.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995, told one twelve-inch record at a time.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

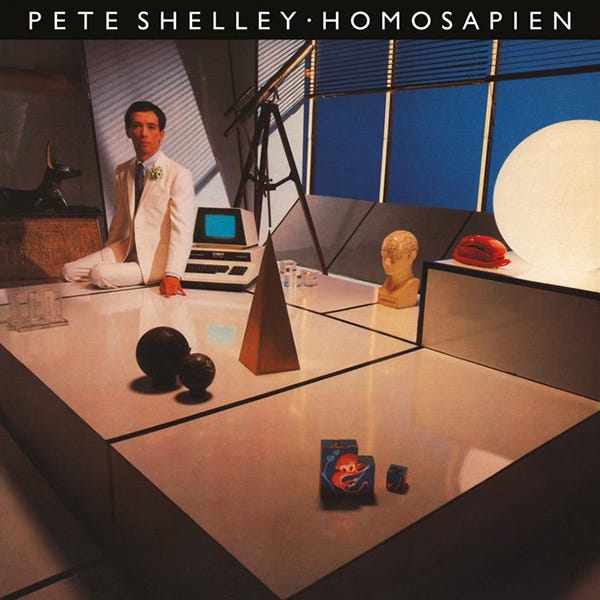

Homosapien, Birth of a Sound 🧬🎧

When Martin Rushent brought Pete Shelley to his new Genetic studio in February 1981, the two began cutting tracks using Fairlight, Roland Microcomposer and drum machines, with Shelley handling all guitars and vocals himself.

Pete Shelley:

What started out as “demos” very quickly evolved into fully realised recordings. Shelley later recalled that, after just a few months, three tracks already sounded ready for release.

Pete Shelley:

Through this process of experimentation, Rushent and Shelley not only found the ideal sound for Pete’s first solo album, they also laid down the blueprint for the sound that would define much of Martin Rushent’s production work in the early eighties, exerting a huge influence on what we now know as synth-pop.

And yet, when asked which album best represents this new sound, most people would answer The Human League’s Dare, not Pete Shelley’s Homosapien. In other words, while Rushent’s synth-pop method may have been born on Homosapien, the public first encountered it ,fully formed, via Dare.

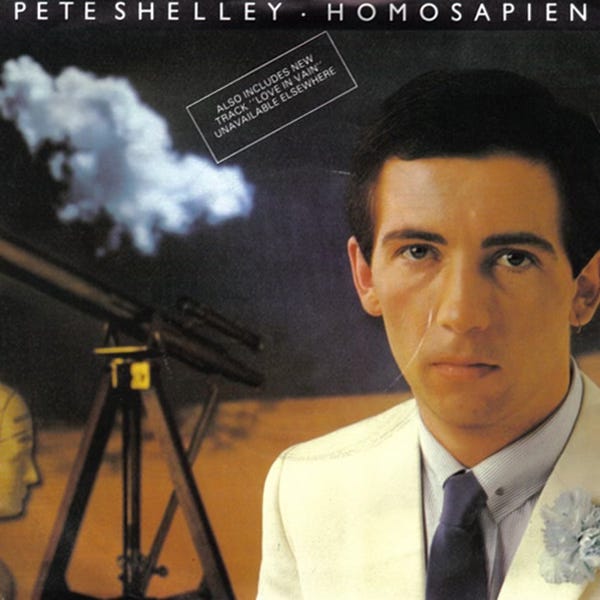

Several overlapping factors explain why Dare, rather than Homosapien, became the headline launch of Rushent’s synth phase. Much of it revolves around Pete Shelley’s first single, the title track “Homosapien,” and the alleged homosexual nature of its lyrics, which resulted in a ban by BBC Radio 1.

Pete Shelley was signed to Island Records via Rushent’s Genetic label, while The Human League were signed to Virgin. When Shelley’s first single hit a brick wall in the UK, Island chose to delay the album, hoping another single might fare better. But because the track did gain traction in a few territories, they couldn’t immediately abandon it. As a result, Pete Shelley’s album was quietly put on the back burner. The fact that the material originated as Buzzcocks demos, that now had to be repositioned as a solo album, only complicated matters further.

Virgin, by contrast, faced no such hesitation with The Human League. “The Sound Of The Crowd,” “Open Your Heart,” and “Love Action” became major hits, paving the way for the ultimate UK number one, “Don’t You Want Me.” The momentum behind Dare was enormous, and the sense that it represented a bold new sound only amplified its impact.

Crucially, The Human League offered Rushent a young, image-driven group that could confidently front a polished pop record on television and in music videos, something Shelley, coming from punk and with a far more explicitly queer lyrical stance, could not do as easily in the UK mainstream media of 1981.

So while Homosapien technically came first in the studio, Dare was the safer, more obviously bankable pop vehicle, and therefore the one a major label could rush to market, as the flagship of Rushent’s “new sound.”

What makes the story even more striking is that Martin Rushent and Pete Shelley had, in a sense, set the “Human League competition” in motion themselves. They initially offered the Shelley recordings to Virgin, who had no interest in signing Pete Shelley but loved the sound. At the time, Virgin were actively looking for a new producer for The Human League.

The Ban, The Shift, The Consequences 🚫📻

The song Homosapien was banned by the BBC, for its alleged “explicit reference to gay sex.” The objection centred on the lyric in which Pete Shelley sings “homo superior / in my interior.” Shelley later explained that the line was never meant as innuendo, telling The Advocate:

“In my naivete...I neverthought it would be taken for a description of sex. I try not to make my lyrics obscene.”

A close reading of the lyrics reveals, far more than in earlier Pete Shelley songs, clear homosexual undertones. Yet, these are directed less toward sexual provocation than toward questions of society, expectation, and acceptance. In that sense, Homosapien serves as a poignant reminder of where gay rights and visibility stood in the early eighties, before the onslaught of AIDS would once again reshape public perception.

Take a verse like:

It captures, with remarkable grace, the inner conflict of loving someone of the same sex: on the one hand, the relationship feels right, natural, and affirming, while on the other, there is the painful awareness that society is not yet ready to accept it.

At the same time, the song holds on to a quiet but powerful hope, the belief that things might change, that acceptance will grow, and that one day it simply won’t matter anymore.

The song is at least as much, if not more, about human tenderness than about who you are shagging. At its core, it is a plea for acceptance. In the case of Frankie’s Relax, I can understand why the BBC chose to ban the song, not that it was the right decision, but the reasoning is at least clear. If there was any doubt about the lyrics of that song, the video spelled everything out very plainly.

With Homosapien, however, we can safely say that the decision was a far stranger one. Having lived through that period, I can understand the broader climate in which it happened, but I’m also convinced that many of those loudly defending the BBC’s stance, hadn’t actually read the lyrics, or didn’t fully understand what they were reacting to.

Lyrics, Longing & Acceptance 💬💞

So what, then, separates Homosapien from the earlier Buzzcocks songs, written by Pete Shelley? The most obvious point of comparison is the band’s biggest hit, “Ever Fallen In Love.”

That song distilled the universal ache of unrequited longing into a spiky, irresistibly melodic pop form. Although Pete Shelley wrote it about a relationship with another man, the song itself is deliberately gender-neutral. It captures the state of someone deeply confused, confused about sexuality, confused about love, confused about desire.

“I tried to be as gender neutral as possible in writing songs, because for me I could use the same song for either sex,” said Shelley

And yet, if you’re part of the LGBTQ+ community, “Ever Fallen In Love” can read as even more overtly gay than “Homosapien.” That is the quiet genius of Pete Shelley’s songwriting: his songs offer solace to everyone without ever losing their specificity or emotional truth.

Understanding how Shelley grew up musically within the Manchester punk scene, and how his own bisexuality was never treated as an issue there, helps explain why he felt free to write the way he did, and why he hoped punk’s liberating ethos might extend into wider society. From that perspective, it also becomes clear why Homosapien moves a step further, becoming slightly less neutral and more explicit than his earlier work.

Pete Shelley’s “Homosapien” didn’t single-handedly rewrite the rules around sex and homosexuality in pop, but it did emerge as a strikingly early synth-era template for openly queer-coded desire, within an otherwise hetero-dominated mainstream.

“Homosapien” functions as a kind of bridge: a former punk frontman, now fully immersed in synth-pop, singing a first-person love and sex song that is unmistakably boy-to-boy — “I’m the shy boy, you’re the coy boy” — while still retaining gender-neutral phrasing elsewhere. Its mix of club-ready electronics and unambiguous queer charge, ensured heavy rotation in gay discos and on MTV, even as it remained banned by the BBC.

Rather than inventing queer pop from scratch, the song crystallised a direction that new wave and post-punk were already moving toward: sex and desire voiced from a queer perspective but framed as a universal “you and me” romance. There is a defiant insistence that “the world is so wrong,” and that love between “you and me” must stand firm in the face of hostility — a stance later critics would read as an act of solidarity against homophobia. Central to this is the idea of “homosapien” itself: a shared category that simultaneously rejects and reclaims identity labels.

In terms of influence, “Homosapien” is best understood not as a direct blueprint for later hits, but as part of a broader lineage that made explicitly queer club records viable in the mainstream.

Here, is an openly gay artist singing a song with blunt, if technically deniable, gay overtones. That ambiguity wasn’t unusual on MTV, but Shelley pushes it further than most. “Homosapien” nudges right up against the boundary without quite crossing it. It teases the listener, dares them to consider that this might indeed be a gay love song, and leaves that possibility hanging in plain sight.

Crucially, this provocation resides in the song itself, not the video. The video was designed to soften the song’s bluntness, offering a kind of visual alibi. Ultimately, it’s a masking job, but a mask that was always meant to be seen through.

Legacy, Influence & Aftermath 🌍✨

Strangely enough, neither the single nor the album, charted in the UK at all. Considering that Pete Shelley came from one of the most successful punk bands of the era, and that Homosapien effectively laid the groundwork for the hugely successful Human League album Dare, this is nothing short of astonishing.

At the time, the record industry, as it so often did, used the UK as the primary yardstick. European Island Records subsidiaries and distributors typically waited to see domestic UK results before committing to support a release in their own territories. As a result, faltering on the home market had severe consequences for continental Europe. In practical terms, that means Homosapien failed to chart in any European country. There is, admittedly, that strange, long-tail success attached to another track, “Witness The Change,” but that is a story for another episode.

The only places where Homosapien did chart were English-speaking territories outside the UK. It became a Top 10 hit in Canada and Australia, and narrowly missed the Top 10 in New Zealand. Meanwhile, the song’s excellent dub version found its natural home on, presumably, gay dancefloors in the US, pushing the track to number 14 on the US dance charts. So there was definitely a potential.

And here’s the real kicker: with a story like this, you might expect plenty of bad blood and unresolved conflict, among the people involved. Yet I found nothing of the sort. On the contrary, Martin Rushent and Pete Shelley continued working together, reuniting for Shelley’s next solo album, XL1. Both were genuinely proud of what they had achieved with Homosapien. They understood that the BBC ban set the course the record ultimately followed, and that this outcome was largely beyond their control.

The clearest proof that Pete Shelley himself still believed deeply in the song came in 1989, when he re-released it as Homosapien II, remixed and retooled for the late-eighties, early house sound, yet every bit as potent as the original.

A Perfect Storm, Not a Failure 🌪️🎛️

So, could Pete Shelley ever have been as big as The Human League’s Dare? Maybe. Possibly. Had the BBC ban not happened, the odds would certainly have been better. But at the same time, we shouldn’t overstate the ban’s importance. Yes, it was frustrating, and it was the key reason why Island Records hesitated while Virgin seized the initiative, but it wasn’t the only factor at play.

Shelley was emerging from a punk background, and his move toward danceable electronic music required a complete reinvention. That, more than anything else, is likely why Homosapien failed to chart and why he didn’t benefit from the same kind of “protest momentum” that Frankie Goes To Hollywood would ride to massive success just a few years later.

In short, Pete Shelley’s Homosapien was caught in a perfect storm and never had the chance to realise its full commercial potential. His solo career, however, was far from a failure, something I’ll return to in future posts. And he felt the same way. In what was probably his final interview in June 2018, an audience member asked: “I really like your solo albums and at the time I was really annoyed that they weren’t bigger and that more people didn’t really seem to get them. Did it frustrate you too?” Pete replied, “Probably not as much as the record company.”

Nor were all bridges burned with his former Buzzcocks bandmates. They reunited toward the end of the eighties and went on to enjoy a successful second chapter.

Shelley’s influence is unmistakable in artists as iconic as Morrissey, whose songwriting clearly echoes the Buzzcocks’ blend of sardonic self-deprecation and the delicate untangling of sexuality and loneliness through language that is simple on the surface, yet brilliantly evasive underneath.

I’ll return to several topics we touched on in this episode — The Human League and Heaven 17, the curious yet enduring success of the non-single “Witness the Change,” and Pete’s later career.

But what about Pete Shelley today?

In the same June 2018 interview, someone in the audience asked whether he had a song he’d like played at his own funeral. He said he didn’t — and joked he wasn’t planning on dying anytime soon. Sadly, just six months later he passed away from a suspected heart attack while living in Tallinn with his second wife.

Thanks for reading The Twelve Inch! This post is public so help us grow the community by sharing it. Thanks for the support!

💬 Over to you, dear reader…

Did you know Homosapien before this story, and if so, how did you first encounter it, radio, club, record shop?

Do you hear it more as a synth-pop record, a queer statement, or simply a love song?

Do you think the BBC ban stopped the record in its tracks, or was the real issue Pete Shelley’s leap from punk to electronics?

And finally: which Pete Shelley or Buzzcocks song means the most to you, and why?

I’d love to read your thoughts, drop them in the comments and let’s continue the conversation.

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Youtube. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

This week’s set is a real early-eighties dancefloor gem, packed with synth-pop, alongside touches of post-punk and early new wave. I kick things off with three Martin Rushent productions: a mix of the single and dub versions of Homosapien, followed by the dub of The Human League’s “Seconds”, and Rushent’s excellent twelve-inch mix of Altered Images’ “I Could Be Happy.”

Along the way, you’ll find strong club cuts from Thomas Dolby, Visage, Soft Cell, and Heaven 17, paired with deeper selections by Paul Young, Shriekback, The B-52’s, and The Associates. There’s also a Belgian connection, with two tracks that once ruled the early dancefloors in my sets: “The Fashion Party” by The Neon Judgement and the uplifting “Allez Allez” by Allez Allez.

I close the set with two absolute blockbusters: Duran Duran’s “Hold Back The Rain” and Gary Numan’s “Cars.”

Enjoy! 🎶

Next week, we’re going very obscure, at least for American and English-language readers. I’ll be telling the remarkable and little-known story of one of France’s biggest artists, who went on to sign with Atlantic Records in the US, recorded three albums in English, and saw one of them, a soundtrack, turn into an unexpected club hit in 1976.

I know what I'm listening to on my dog walk later!

As a Buzzcocks fan, I was excited that Shelley was doing his tuneful, clever thing in a different musical context. As far as queer content, at the time, I saw it as a smart rebuke to those who would have a knee jerk reaction to any word starting with “homo,” among other things. Do your other question, it’s hard to pick a favorite Buzzcocks song, but the perfection of You Say You Don’t Love Me is tough to beat!