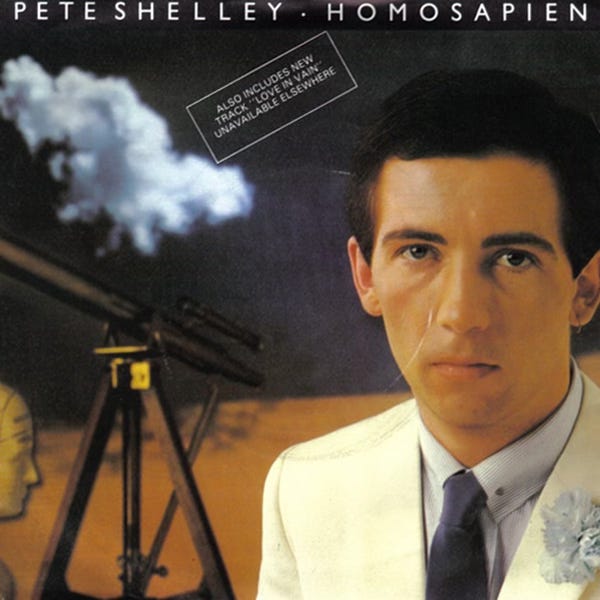

🌈🎛️ Homosapien by Pete Shelley, Punk, Synths & Liberation

The Twelve Inch 201 : Homosapien (Pete Shelley) Part 1

This week’s newsletter turned out to be a big one again, so I’ll be publishing it in two parts. Today’s first episode sets the scene. Next Friday, I’ll dive into the specific story of the song. The read-aloud version will tell the full story in one go and will be included in part two, next Friday.

The great thing about writing this newsletter is that you get the opportunity to, via the research, get much closer to the artists you like & write about than ever before. Usually, it ends up with a lot more respect for the person behind the artist and what they’ve achieved, often in times that were anything but easy.

Occasionally, the opposite happens, or I end up loving the artist a lot more than when I started the research.

This week is clearly one of the latter.

I knew Pete Shelley mainly from one of those early-eighties records I kept playing in my sets, even many years after its original release. “Witness The Change” is probably known by all of my peers, but strangely enough mostly in the Dub version (and I even doubt if many know that the original is a sung version 😂). That’s a story for another time.

Today, I go deeper into Pete Shelley’s first solo single: Homosapien. It’s the one that was blacklisted by BBC Radio 1 in the UK, a decision not unlike what would happen to Frankie Goes To Hollywood a few years later.

But where the ban helped Frankie break through and become one of the most popular UK acts of the eighties, it had the opposite effect on Pete Shelley.

Homosapien was destined to be a hit. A big hit. Instead, it went nowhere and made his solo career start with a whimper. The consequences were huge: the new sound Pete Shelley helped develop was instead used for The Human League’s Dare album, propelling them to world fame rather than Shelley.

Based on this introduction, you might expect a story full of fighting and bad blood. Strangely enough, that is not the case.

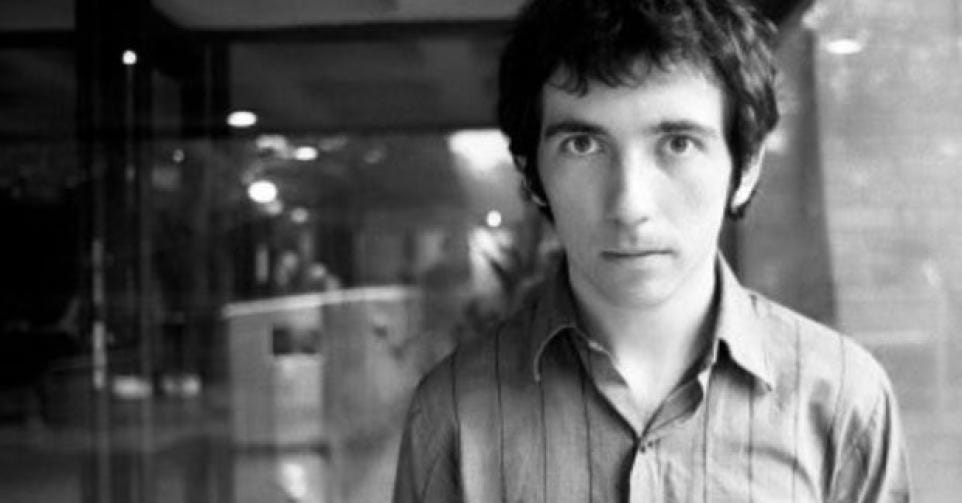

That, perhaps, is the most important reason why my love for Pete Shelley grew considerably, while researching and writing this piece. I’m sure he wasn’t fun all the time, but I do think he was fun most of the time. His quotes and interviews point to a genuinely warm, kind human being, on top of being a very talented artist and songwriter.

The second reason I came to admire him so much is his sexuality. Pete Shelley was bisexual. He was married twice, yet wrote beautiful songs about homosexual love.

And here’s the beauty: they weren’t in your face. That subtlety makes them even stronger today. The first example is the biggest hit of his band The Buzzcocks, “Ever Fallen In Love (with Someone You Shouldn’t Have)”, which many people know best through The Fine Young Cannibals’ version.

The reason I love this song so much is that you can apply the lyrics to your own life, whatever your sexual preference. We know Shelley wrote it during a male-male relationship, and even know who it was for. But he deliberately left the gender open, allowing everyone to project their own experience.

The second example is Homosapien. It’s a bit more explicit, but compared to Relax, it’s practically Wiener Sängerknaben repertoire. Which makes the Radio 1 ban even more incredible.

So why was Homosapien banned?

What did that ban do to Pete Shelley’s career prospects?

Why did The Human League, and not Shelley, benefit from the new sound developed in producer Martin Rushent’s studio?

And how important is Homosapien for queer emancipation?

Fasten your seatbelts. We’re off on a Time Machine ride to 1981, to the industrial heartland of the UK.

👋 Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre, thanks for stopping by.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995, told one twelve-inch record at a time.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

Punk, Disco & Personal Paths ⚡🪩

I wasn’t into punk when I was young. Obviously, if you’re writing every week about disco or eighties dance music 😂. But I did love the energy.

Last week, I wrote about not really knowing what tipped me into becoming a disco fan instead of following what my peers listened to (which wasn’t punk either, more classical or prog rock). What’s true is that musical preference develops in stages, and even under the same circumstances, reliving the period wouldn’t guarantee the same outcome.

I thought about this when reading Shelley’s quotes on punk and its “entente cordiale” with the gay scene. Disco played a role in my own coming out. It could just as easily have been punk.

Buzzcocks, Manchester & Liberation 🎸🏭

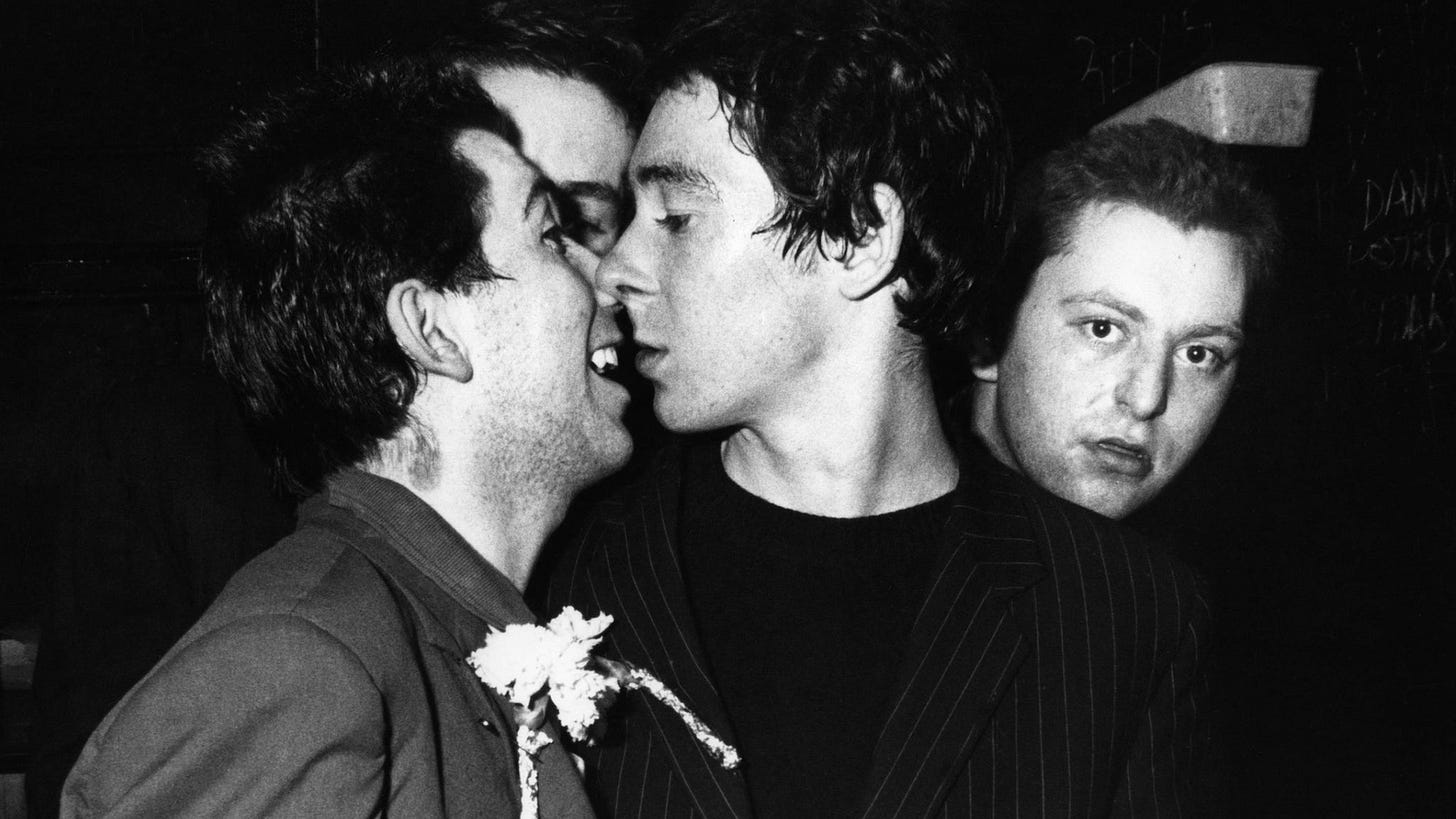

Pete Shelley was the singer of one of the UK’s top punk bands: The Buzzcocks. Their story is intertwined with The Sex Pistols, and they were central to the development of the Manchester scene in the late seventies and early eighties.

Though punk is often seen as macho, Shelley never felt the need to hide his sexuality. Manchester punk was about new ideas and attitudes, and embraced everyone.

“It didn’t really matter what you were, what sexual persuasion you were from or what gender you were,” Pete Shelley said.

“It didn’t really matter, it didn’t raise eyebrows if someone was gay.”

Another revelation for me was that punk was fundamentally about liberty. Not about being stereotypically rock ’n’ roll.

And the aggression?

From Lancashire to Spiral Scratch 🏭📀

Pete Shelley was born Peter McNeish in Leigh, Lancashire, to Margaret and John McNeish. His mother was an ex-mill worker, his father a fitter. They didn’t have much, but they shared.

In 1976, Shelley met Howard Devoto, and together they formed The Buzzcocks. Both adopted stage names; Pete’s was inspired by his favourite poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

They helped to change music history by releasing one of the first DIY singles, Spiral Scratch (1977), effectively inventing indie. And by organising two Sex Pistols concerts in Manchester early on, they have inspired bands like Joy Division and Smiths

The Buzzcocks stood at the very heart of the emerging UK punk and indie scene, but where contemporaries like the Sex Pistols and the Clash directed their fury at a decaying dominant culture, Pete Shelley turned inward. His songs were less about confrontation and more about true human connection. He wrote about love, which may well have been the most radical, and therefore punk, thing he could do at the time.

With “Ever Fallen In Love”, a punk singer, for the first time, admitted vulnerability openly and without irony. It was a song about being hurt, plain and simple. And if you’ve ever nursed a broken heart, and you have, the Buzzcocks had already written a song for you.

After a short but brilliant run, the band hit a wall after their third album in 1979. The enthusiasm was gone.

Enter Martin Rushent 🎛️🧠

Our second key figure is producer Martin Rushent. He began as a tape operator alongside Tony Visconti, working with Fleetwood Mac, T. Rex, Yes, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Petula Clark, Jerry Lee Lewis and Osibisa. After rising through the ranks to head engineer, he began working freelance. It was during this period that he was engaged by United Artists. The Buzzcocks were also signed to United Artists, which is how Martin Rushent came to produce their albums.

By the end of the seventies, however, tired of the constant commute to London and of producing guitar bands almost exclusively, Rushent began setting up his own studio, “Genetic,” in Berkshire. At that point, he “started investigating new synthesizer and sequencer technologies,” bought a Roland Micro Composer (MC-8) after seeing it advertised, and “bought a Roland Jupiter synth to go with it and started experimenting.”

In parallel, he soon added a Linn LM-1 drum machine and other high-end digital instruments, including the Synclavier and Fairlight, as Genetic took shape around 1980. He was drawn to what electronics newly made possible. It was the logical next step once he had his own studio and no longer had to cater to label expectations.

The precision and control of programmable gear were exactly what he felt guitar sessions lacked.

Shelley, for his part, had already experimented with electronics, even recording a full electronic album (Sky Yen) before the Buzzcocks, though it remained unreleased at the time.

A Creative Symbiosis 🔮🎶

Pete Shelley and Martin Rushent loved working together.

In 1980, work was due to begin on the fourth Buzzcocks album, once again with Martin Rushent producing. Rushent quickly realised that, one way or another, nothing releasable under the Buzzcocks name would happen unless Pete Shelley felt inspired to work. At that point, Pete had little enthusiasm for his own songs, and even less for Steve Diggle’s.

Rushent’s drastic solution was to halt recording altogether, supposedly to give Pete time to demo some new material. This pause was presented to the rest of the band as a two-week break.

Shelley and Rushent then decamped to Genetic Studios to work. While there is disagreement among those involved about exactly when the shift occurred, what is beyond dispute is that the sessions quickly stopped being about demos for a new Buzzcocks album and became the foundation of Pete Shelley’s solo career. Shelley clearly found the new set-up liberating, although at first he had no idea he was working toward finished recordings rather than rough demos.

Steve Diggle (Buzzcocks’ guitarist):

The rest of the band only discovered that the Buzzcocks no longer effectively existed when they received solicitors’ letters on 4th March. By then, Pete Shelley had already recorded a full album and signed a solo deal with Rushent’s Genetic label.

The stage is set for next week’s action. We’ll zoom in on how the recordings became the blueprint for Human Leagues “Dare” album and why Pete Shelley helped create that new sound but didn’t enjoy in any of its benefits. I’ll explain why the BBC banned the song and if they had reason to. And I’ll zoom in on the importance of Homosapien for the eighties synth-pop music and queer emancipation.

Thanks for reading The Twelve Inch! This post is public so help us grow the community by sharing it. Thanks for the support!

💬 Over to you, dear reader…

Did you know Homosapien before this story, and if so, how did you first encounter it, radio, club, record shop?

Do you hear it more as a synth-pop record, a queer statement, or simply a love song?

Do you think the BBC ban stopped the record in its tracks, or was the real issue Pete Shelley’s leap from punk to electronics?

And finally: which Pete Shelley or Buzzcocks song means the most to you, and why?

I’d love to read your thoughts, drop them in the comments and let’s continue the conversation.

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Soundcloud. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

This week’s set is a real early-eighties dancefloor gem, packed with synth-pop, alongside touches of post-punk and early new wave. I kick things off with three Martin Rushent productions: a mix of the single and dub versions of Homosapien, followed by the dub of The Human League’s “Seconds”, and Rushent’s excellent twelve-inch mix of Altered Images’ “I Could Be Happy.”

Along the way, you’ll find strong club cuts from Thomas Dolby, Visage, Soft Cell, and Heaven 17, paired with deeper selections by Paul Young, Shriekback, The B-52’s, and The Associates. There’s also a Belgian connection, with two tracks that once ruled the early dancefloors in my sets: “The Fashion Party” by The Neon Judgement and the uplifting “Allez Allez” by Allez Allez.

I close the set with two absolute blockbusters: Duran Duran’s “Hold Back The Rain” and Gary Numan’s “Cars.”

Enjoy! 🎶

Next week, I’ll publish part 2 of the story of Pete Shelley’s Homosapien

Wow!! So much new for me here!! I’d only heard of Pete Shelley in relation to one song he had on the soundtrack to the 1987 movie “Some Kind of Wonderful”. Obviously, this was pre-internet and I had no clue who Pete Shelley was. Given how many small and obscure artists appeared on the soundtrack, I probably assumed he was a small independent artist who hafn’t ever really done much. WRONG!!

I’d also been aware of The Buzzcocks and knew the track “Ever Fallen in Love” but I never knew Pete Shelley was the lead singer or quite how influential The Buzzcocks were. And I never knew anything about Shelley’s solo career outside of the one track I mentioned above.

I enjoyed the track Homosapien and am really looking forward to giving the album a listen and tuning in to part two of this story!!

I can already tell you I cannot wait for Part 2. Particularly the banning of the song (sadly, the BBC has a penchant for censoring and/or manipulating information).

I loved reading more about your relationship with punk, and how Pete Shelley simultaneously embraced his bisexuality and his punk fire.

The way this newsletter blends personal stories, historical rigour, socio-cultural implications, record industry insights, and your passion for music is extraordinarily brilliant in every single respect. Chapeau 🎩