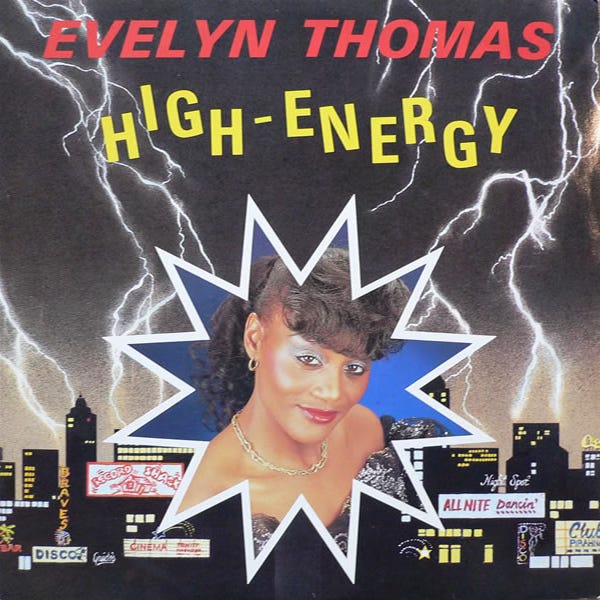

⚡️High Energy: Evelyn Thomas, Ian Levine & the Birth of Hi-NRG — Part 1

The Twelve Inch 193 : High Energy (Evelyn Thomas) Part 1

You’d think a song called “High Energy” would be easy to label. But it really isn’t. At roughly 120 BPM, it barely meets the usual definition of Hi-NRG. I know that’s a minority opinion, but it’s true. Still, the track became one of the biggest and most influential dance records of the mid-eighties. It was part of the remarkable year 1984, arguably the most queer year in dance-music history. The single sold an estimated 7 million copies, and if the stories are accurate, Evelyn Thomas saw little to none of that success in financial terms.

“High Energy” would go on to name an entire genre, a sound that became central to the gay dancefloor and has stayed there ever since. It also arrived just after Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s first hit, “Relax,” and in many ways mirrors its structure and energy. For producer Ian Levine, “High Energy” stands as the most iconic moment of his career, a peak for one of Britain’s most influential dance-music creators.

The forces that shaped the record were already in motion: Northern Soul, Brit-Funk, and Euro-disco all created the perfect conditions for Levine to deliver this breakout hit. In this episode(s), I’ll explore the careers of Ian Levine and Evelyn Thomas, trace the early development of Hi-NRG, and try to answer a simple question: Was “High Energy” actually Hi-NRG?

This will be a two-part post. Today, we’ll set the stage, meet the key players, and look at where Hi-NRG begins.

Let’s plug it in.

👋 Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre, thanks for stopping by.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995, told one twelve-inch record at a time.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

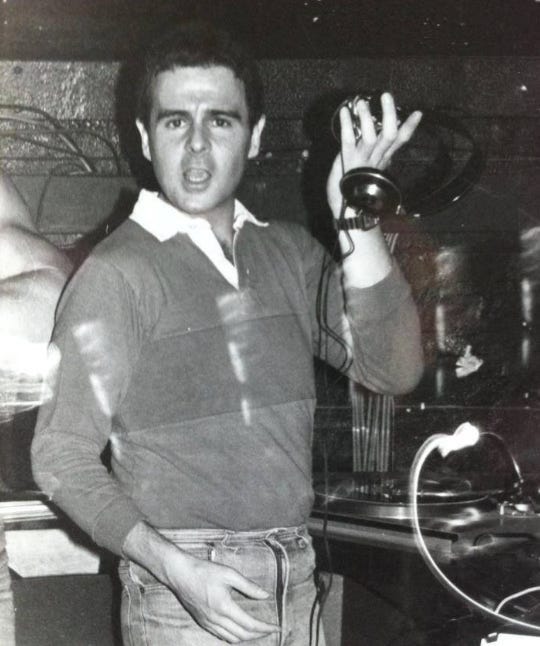

🕺 Ian Levine: From Northern Soul Basement Hero to Hi-NRG Architect

We can’t tell the story of Evelyn Thomas and “High Energy” without first looking at the man behind it: producer, DJ, and dance-music entrepreneur Ian Levine. Evelyn Thomas spent most of her career working with him.

Ian Geoffrey Levine was born on 22 June 1953 in Blackpool. His parents ran the Lemon Tree complex, which included a nightclub and a casino. Growing up in that environment, it’s no surprise that he became a DJ after leaving school in 1971. Levine was also a passionate collector of American soul records (he had a collection of 50.000+), exactly the kind of music that powered the Northern Soul scene spreading across Northern England and the Midlands in the early seventies.

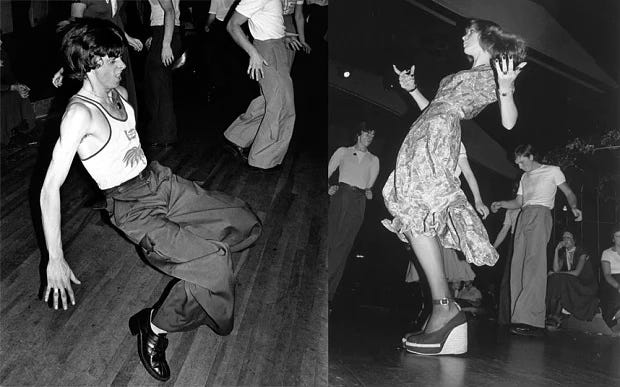

Northern Soul grew out of the Mod movement. It focused on a specific strain of Black American soul: fast, driving, and often released on small labels in tiny quantities. Fans generally avoided mainstream Motown hits, favouring rare grooves by little-known artists. The scene developed its own ecosystem of dances, fashions, and all-night rituals at clubs like the Twisted Wheel in Manchester, Wigan Casino, the Highland Room at Blackpool Mecca, and the Golden Torch in Stoke-on-Trent.

As tempos climbed in the early seventies, Northern Soul dancing became increasingly athletic, full of spins, drops, kicks, and moves inspired by the stage shows of touring American soul acts. The records themselves usually came from the mid-sixties, which meant DJs kept the scene alive by digging up obscure singles that had slipped through the cracks.

Levine quickly realised he wanted to do more than play records. With the supply of undiscovered rare grooves drying up, he saw an opportunity: why not make new ones? He persuaded his father to invest in a production company, with the idea of recording American soul singers and licensing the results to major labels. That search for talent took him to Chicago.

And that’s where he met Evelyn Thomas.

🌟 Evelyn Thomas: Chicago Soul Meets European Synths

Evelyn Thomas was born in Chicago on August 22, 1953. Like many African American singers, she started out in church, but her powerful voice never quite suited the blend of a choir. By 1975, after some early studio work and time on Broadway, she heard about an English producer in town looking for new talent. That producer was Ian Levine.

Her audition wasn’t straightforward. Levine wasn’t interested at first—he’d already signed Barbra Pennington and didn’t think he needed another female vocalist. But his Chicago production partner, Danny Leake, pushed him to give Thomas a chance. She had two minutes to impress him. She needed far less. Levine signed her on the spot.

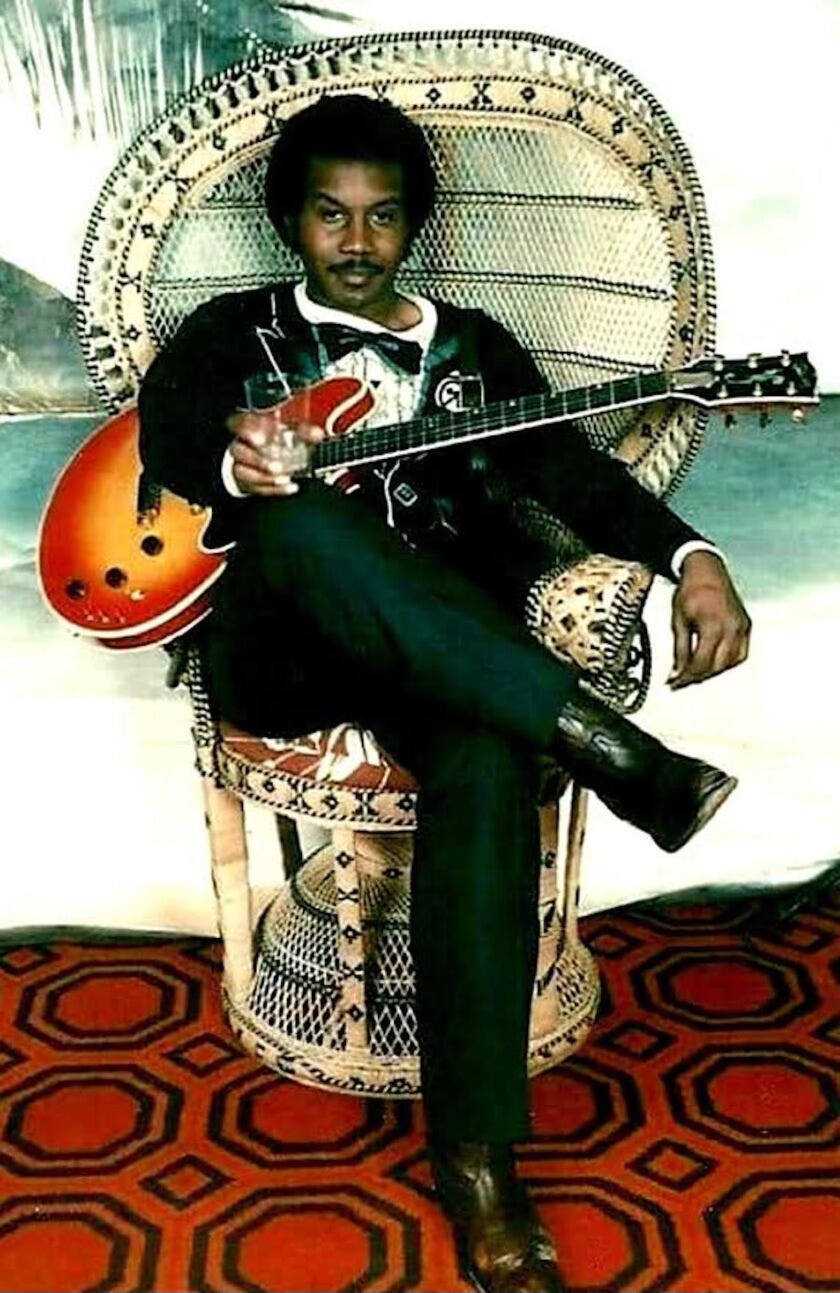

Danny Leake

Their first collaboration produced several tracks, including “Weak Spot,” which reached number 26 in the UK Top 40 in 1976. But the production company struggled. The hoped-for hits didn’t arrive, and cashflow became a problem. Levine licensed a batch of Thomas’s songs to Casablanca Records, who released the album with no proper single or promotion. A second set went to AVI Records, but by then the disco backlash was underway, and the results were again disappointing.

It wasn’t until 1983 that Levine and Thomas reunited for another set of recordings.

This time, it would work.

🌍 From Soul to Synthesisers

By the late seventies, the Northern Soul scene was starting to stagnate. Dancers wanted something new, but the purists resisted anything recorded after 1969. Ian Levine, meanwhile, was getting pushback for playing his own new productions in his DJ sets. Critics accused him of making records “tailor-made” for the scene, and the resentment grew into a full campaign: “Levine Must Go.”

Another turning point came when Levine began visiting New York’s gay discos. There he found a vibrant, creative club culture where DJs and producers openly made new tracks specifically for the dancefloor, a sharp contrast with Northern Soul’s strict gatekeeping. Combined with the hostility he faced back home, this pushed Levine away from Northern Soul and toward disco and Brit-funk.

His next move was to a new London club that opened in 1979: Heaven.

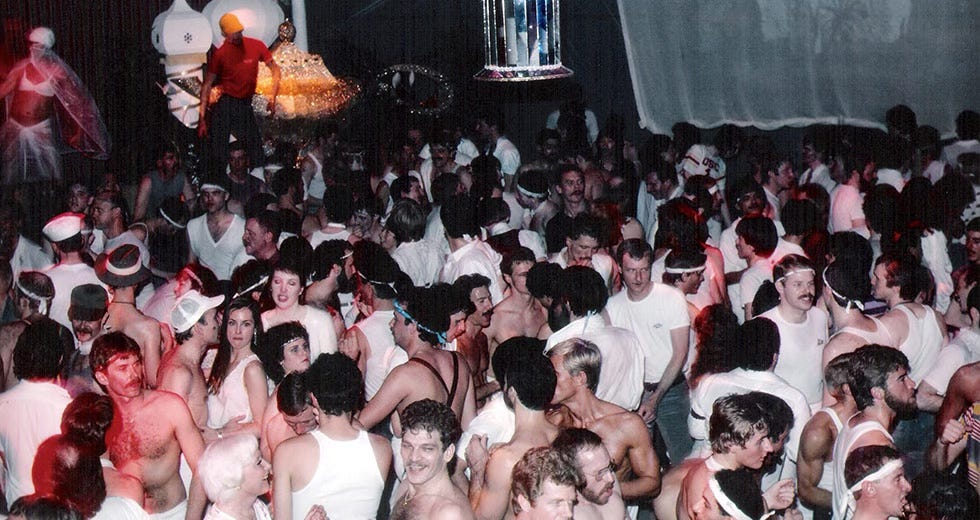

Heaven became to London what The Saint was to New York, a central gay nightlife hub where fast, synth-driven Euro-disco dominated. So when the disco backlash hit the United States in 1979 and mainstream dance music slowed down, Levine saw an opportunity. He could make the high-tempo, high-drama music his gay audience still wanted.

It was the sound that would soon be known as High Energy.

🔋 What Is Hi-NRG, Exactly?

A quick breakdown of the core ingredients

Hi-NRG is one of those genres everyone recognises immediately, even if the definition can feel slippery. At its core, it’s a blend of fast tempos, machine-tight rhythm, and emotionally charged vocals, an electronic extension of disco built for high-impact dancefloors. Here are its essential elements:

Rhythm and tempo

Hi-NRG usually sits between 120 and 140 BPM, with many classic early-80s tracks hovering in the high 120s. The rhythm is rigid and propulsive: a steady four-on-the-floor kick, bright staccato hi-hats, and a sharp snare on the 2 and 4. It’s built for drive, not swing.

Basslines and synths

The basslines are unmistakable, sequenced, octave-jumping, and clearly descended from the Giorgio Moroder school that shaped “I Feel Love.” They’re tight, arpeggiated, and machine-precise. Synthesizers and drum machines dominate, giving the music its bright, metallic, high-voltage character, harder and more electronic than ’70s disco or early-’80s boogie.

Melody, harmony, and vocals

Structurally, Hi-NRG sticks to strong pop songwriting: clear verses, big choruses, and dramatic middle eights. Vocals are powerful and often belted, usually female divas or theatrical male singers, delivered with reverb and emotional punch rather than subtle phrasing.

It’s disco sped up, tightened, and electrified: music engineered for intensity.

🌈 The Evolution and Spread of Hi-NRG

👉 Where It Started

The shift toward what would become Hi-NRG had been underway since Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” rewired dancefloors in 1977. As disco evolved, it moved further away from its R&B roots and Black-identified textures, favouring spacier synths, faster tempos, and more mechanical beats. But the fully formed Hi-NRG sound didn’t emerge in London, or even New York.

It began in San Francisco.

One of SF’s most important clubs : The Trocadero Transfer

San Francisco was second only to New York in developing a gay dance culture, but it had its own identity. The legacy of the 1960s counterculture, combined with a largely white, college-educated, middle-class crowd, created a highly performative and self-contained scene, far removed from the grit and chaos of New York nightlife. That insulation also meant the city was less affected by the “Disco Sucks” backlash of 1979.

The San Francisco sound took shape in 1978, driven by four key figures: Marty Blecman, Patrick Cowley, John Hedges, and Sylvester. Their music grew out of the world of the Castro, and two labels, Megatone Records and Moby Dick Records, became central to it. What they released was fast, electronic, and clearly rooted in Eurodisco, but with a distinctly local intensity.

The electronic nature of the music had practical and artistic roots. With the market shrinking after the disco crash, synthesizers and drum machines made production quicker and cheaper. At the same time, producers wanted to build a futuristic, fantasy-driven world, and electronic instruments provided that palette. But in San Francisco, the machines weren’t used for cold futurism, they were used for euphoria.

Patrick Cowley became the sound’s defining architect. His synth work on tracks like “Menergy” and “Megatron Man”is the true foundation of the Hi-NRG aesthetic: bright, relentless, and charged with a kind of ecstatic voltage.

At its core, Hi-NRG is disco reduced to its essentials: no strings, no lush arrangements, none of the ornamental decadence of the late ’70s. What remains is a kind of electronic blues, man-machine music built for momentum rather than subtlety. It quickly became the default soundtrack of gay nightclubs and sex bars, perfectly matching the rise of the so-called “clone” aesthetic: uniform, hyper-masculine imagery that dominated the era.

For a moment, the future seemed wide open. And then AIDS hit.

Within a few years, many of the creators who shaped the San Francisco sound, Cowley chief among them, were gone. With them went the possibility of sustaining the original scene that had given Hi-NRG its spark. The music lived on, but the world that birthed it would never be the same.

In Part 2, I’ll pick up the story where we left off. What happened when San Francisco, cradle of the early Hi-NRG sound, faded from the very genre it helped spark? How do we get from that scene to a singer from Chicago and a producer from Blackpool shaping its biggest anthem? Why isn’t “High Energy” necessarily a Hi-NRG track at all? How central was 1984 to everything that followed? And why does the song sound so much like “Relax” by Frankie Goes to Hollywood?

💬 Let’s Talk

Do you remember where you were when you first heard “High Energy”? Have a story about hearing it in a club, on the radio, or somewhere else?

👉 Hit reply and share your memory. Or wait until part 2 of the story

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Soundcloud. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

You’d think a track called “High Energy” would launch me straight into an hour of pure mid-eighties Hi-NRG, but Evelyn Thomas’s song sits a little outside the norm with its lower-than-expected BPM. So after an opening stretch of mid-80s dance-pop, Kim Wilde, the Pet Shop Boys, even Chris Rea, we dive headfirst into a pure Italo set.

I start with some deeper cuts, but the second half turns into a parade of era-defining anthems: My Mine’s “Hypnotic Tango”, Klein & MBO’s “Dirty Talk”, Fun Fun’s “Happy Station”, and the Moses classic “We Just.”

Enjoy! 🎶

Tomorrow I’ll continue the story of Evelyn Thomas, Ian Levine and the music genre they helped to popularise.

What a fascinating and educational deep dive, Pe! Your unique blend of music industry knowledge, sociocultural considerations and a love for dance music that truly transcends the screen is indeed wonderful. I learn so much from your work. Have a great Friday, and thanks for the continued education!

I didn't think I knew this one at first but the chorus sounds familiar. Does the mix include "Relax" OR was Frankie Goes to Hollywood inspired by this mix?!