🇧🇷 From Paris to Philly: How “Brazil” by The Ritchie Family Set Disco on🔥and 🇫🇷 on It's Way to Become a Disco Powerhouse

The Twelve Inch 188 : Brazil (The Ritchie Family)

This week I’m chasing an answer to a question that’s been on my mind for a long time:

Why did French artists and producers play such a pivotal role in the birth of Eurodisco?

The list of French successes from that era feels endless, so why France, why then, and why did their influence fade so suddenly when disco began to die in the U.S.? Or… did it really fade at all?

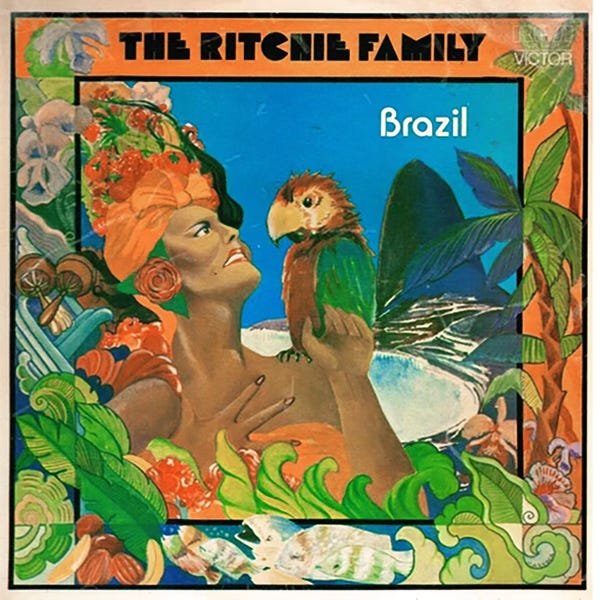

When Saturday Night Fever turned disco from an underground movement into a billion-dollar industry, worth around $4 billion in 1978, European producers were already making their mark. The biggest dance hit of 1975 wasn’t American at all, but “Brazil” by The Ritchie Family: seven weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard disco chart and Top 20 on the Hot 100. It sounded pure Philly, recorded at Sigma Sound Studios with the MFSB/O’Jays/Harold Melvin crew.

But there was one twist: the record was produced by two Frenchmen: Jacques Morali and Henri Belolo.

This week, we’ll trace how their studio project became one of disco’s most successful…