🌤️ Could Heaven Ever Be Like This? Idris Muhammad and the Groove Between Jazz, Funk, and Disco

The Twelve Inch 190 : Could Heaven Ever Be Like This (Idris Muhammad)

Now here’s a name you might not know unless you’re deep into jazz: Idris Muhammad. But if you were going out in 1977, you may have danced to him without realizing it. His luminous floor-filler “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”was a staple at serious New York parties like The Loft or clubs like the Paradise Garage, and later made its way across the Atlantic to the UK’s most discerning dancefloors. Singular, spiritual, and straight-up gorgeous, it’s one of those tracks that can quiet even the most committed disco skeptic.

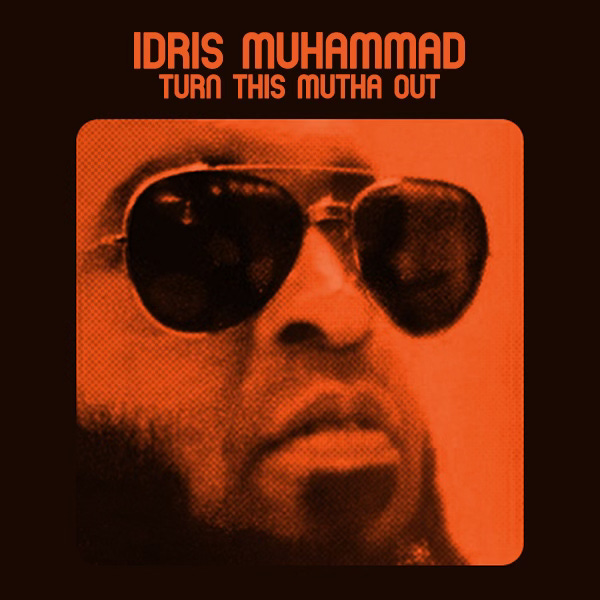

Idris was one of the most gifted drummers of the 1970s, a respected jazz player who refused to be boxed in. Like several of his contemporaries, he crossed over into funk and disco, chasing rhythm and feeling wherever they led. Between 1974 and 1978 he released a run of adventurous albums, but his 1977 LP Turn This Mutha Out, and especially “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”, was his high-water mark.

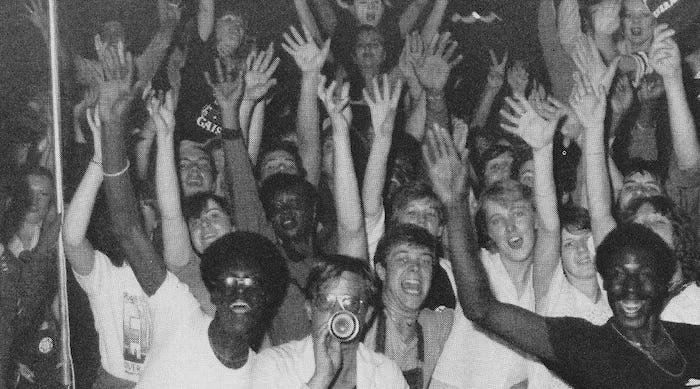

I can’t recall exactly when I first heard it, but like those dancers at The Loft, I was instantly hooked. This isn’t classic disco, it’s what would later be called jazz-funk, a sound that bridged American musicians like Herbie Hancock, Donald Byrd, Roy Ayers, and The Crusaders with a new wave of UK artists. In Britain, that style evolved into Brit-Funk: a scene that transcended racial barriers and united Black and white youth on the dancefloor through groove, melody, and spirit. Bands like Shakatak, Heatwave, Light of the World, Central Line, and Level 42 all carried that torch.

And right at the root of it all was Idris Muhammad’s 1977 masterpiece.

So who was Idris Muhammad? And why don’t we hear his name more often today?

Let’s dig in.

👋 Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre, thanks for stopping by.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995, told one twelve-inch record at a time.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

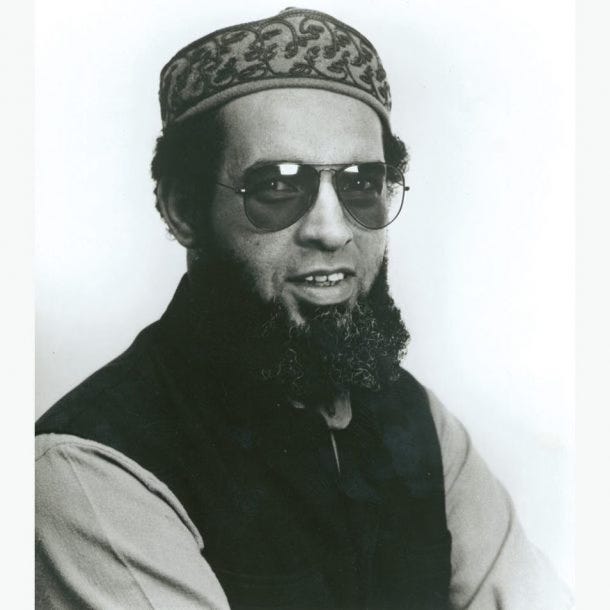

🥁 The Beat Begins: Who Was Idris Muhammad?

Before he became Idris Muhammad, he was Leo Morris, a kid from New Orleans’ 13th Ward who started drumming professionally before he even had a driver’s license. Growing up, second-line rhythms filled the air; music wasn’t just culture, it was oxygen. By 16, he was already behind the kit on Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill.” Let that sink in: one of the most iconic rock ’n’ roll tracks ever made, and its backbeat came from a teenage jazz drummer from Louisiana.

His father, a Nigerian banjo player, and his French mother filled the house with music. Idris and his brothers all played drums, and from early on he developed an ear for rhythm in the most unexpected places, like the machine stomp and hiss of the steam presses at the dry cleaner next door, a sound he said later inspired his distinctive hi-hat touch.

In the mid-1960s, he converted to Islam and changed his name, a move that was as spiritual as it was cultural. Like many African American musicians and public figures of the era, Muhammad turned to Islam for personal empowerment, identity, and community during a time of profound social transformation. Islam became particularly popular with African Americans in the 1960s due to its association with Black nationalism and a rejection of mainstream white American culture and Christianity, which many felt had been complicit in supporting or at least accommodating racial oppression.

By the late 1960s, Idris was already a go-to session drummer, first in soul-jazz, then across the wider jazz and R&B world. He recorded with Sam Cooke, Jerry Butler, Curtis Mayfield, Roberta Flack, and Lou Donaldson, earning respect not just for his precision, but for his feel. Muhammad didn’t just keep time, he reshaped it. His drumming had a kind of weightlessness, a floating funk that made jazz groove like it was built for dancers.

The title track of his 1977 album was the first single and also a hit in the Billboard R&B charts

🎷 From Jazz to Funk to Disco: What Was Idris Muhammad’s Style?

If you tried to pin down Idris Muhammad’s sound, you’d get caught between jazz and funk. The truth is, he lived right in the middle. What he played was jazz-funk, but not the slick, over-fused kind that came later. His records breathed. Every hi-hat, every rimshot felt like part of an ongoing conversation between rhythm and soul.

He came of age in the late 1960s, when jazz musicians were losing the clubs to rock and soul. To stay relevant, many plugged in, literally. Electric pianos, Clavinet basslines, and funk-inspired drumming started showing up in the work of Herbie Hancock, Donald Byrd, and Grover Washington Jr. Idris was part of that same movement, but he never lost the New Orleans pulse that anchored everything he played.

Jazz-funk wasn’t just jazz played funky. It was a cultural negotiation, between improvisation and repetition, between intellect and body, between spiritual lift and street-level groove. And “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” remains one of its purest expressions.

🕊️ “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”: A Jazz-Funk Masterpiece

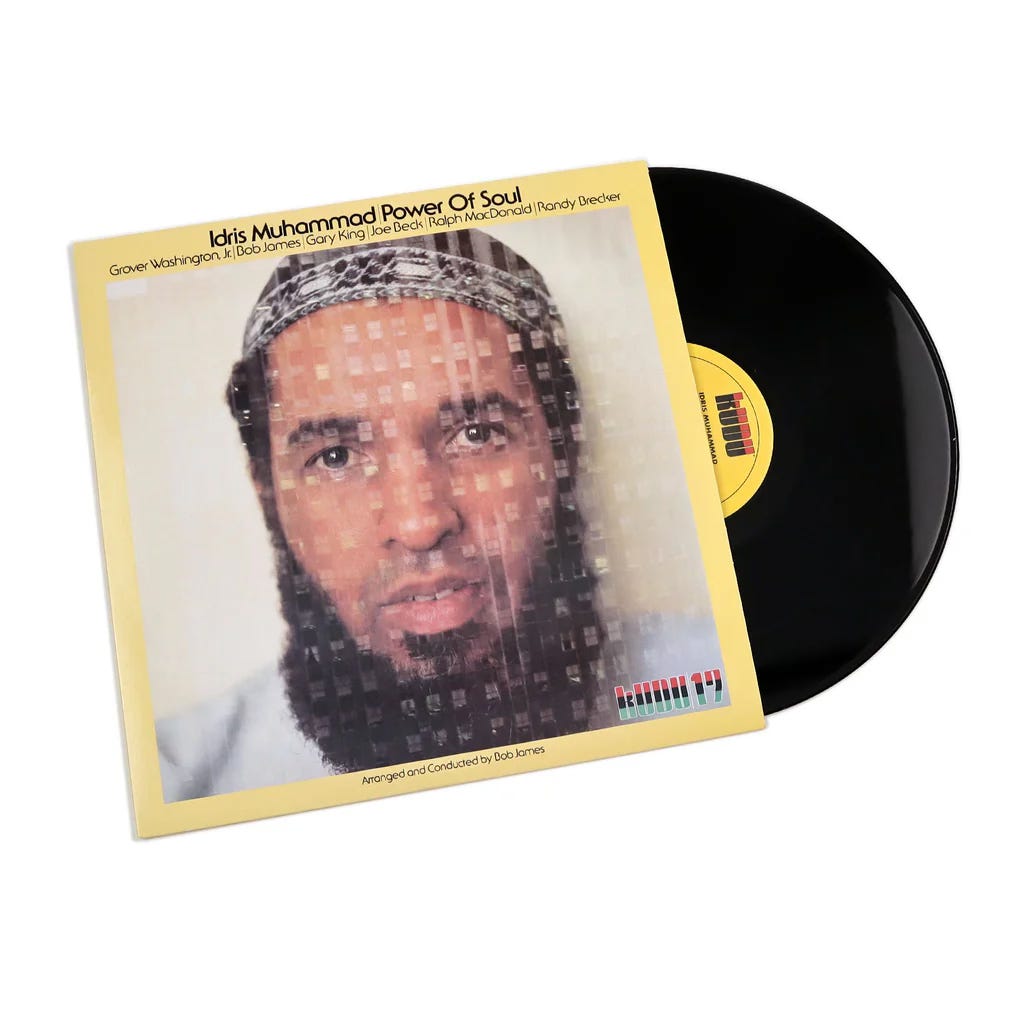

Released in 1977 on Kudu Records, the jazz-funk imprint of CTI (Creed Taylor Inc.), “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” was the product of a team that erased the boundaries between genres.

Written and produced by David Matthews, formerly of James Brown’s band and later an arranger for Nina Simone, Paul Simon, and George Benson, the session pulled together an all-star lineup: Michael Brecker on sax, Randy Brecker on trumpet, and Hiram Bullock on guitar. These were musicians who moved effortlessly between jazz, rock, and pop studio work, shaping the sound of the late ’70s without ever standing still.

The track itself is built on a hypnotic, levitating groove. It opens with shuffling congas, a rising bassline, and cascading synths that feel like a sunrise unfolding in sound. Then come the voices, Frank Floyd and Ray Simpson(brother of Valerie Simpson), asking the eternal question that gives the song its title: Could heaven ever be like this?

💃 Why It Didn’t Break Big in the US Disco Charts

Curiously, “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” never made the U.S. Disco Action charts. Instead, it grazed the R&B listings, a sign that while Black radio embraced its groove, the largely white disco establishment didn’t quite know what to make of it.

By 1977, the dancefloor was ruled by Studio 54 and Saturday Night Fever. The sound of the moment was fast, glossy, and dramatic, strings soaring, tempos racing. Idris Muhammad’s track was something else entirely: spiritual, spacey, and slow-burning. Perfect for The Loft or Paradise Garage, where groove and emotion mattered more than spectacle. But that wasn’t the mainstream.

Part of the issue was its label. Kudu Records was a jazz imprint; its parent, CTI, knew how to reach critics, not club DJs. Disco twelve-inches were moving through Salsoul, Casablanca, and Prelude, labels that understood promo pools, test pressings, and dance charts. Creed Taylor didn’t play that game. The track didn’t need a remix, it was already flawless, but it did need the right hands and networks to spread it.

The other challenge was visibility. The late 1970s music industry revolved around front-facing singers, not drummers or instrumentalists. However brilliant the groove, an instrumentalist rarely broke through to pop stardom.

In the UK, though, things were different. The emerging jazz-funk scene made room for music like this. For British dancers, Idris Muhammad wasn’t a jazz relic, he was the heartbeat of something new. The track even became a near-hit, reaching No. 42 on the UK chart, the only country where it came close to the Top 40.

Late seventies he left Kudu/CTI and signed with Fantasy. This is from his third album of 1980

🌍 The Roots and Rise of Jazz-Funk and how it spread to the UK

Jazz-funk grew out of jazz’s desire to stay connected to the street. It blended jazz improvisation with the backbeat and groove of funk, soul, and R&B, using electric instruments and early analog synths to bridge those worlds. The result was a sound that could stretch from intricate jazz solos to full-on dancefloor workouts, music built for both the mind and the body.

As disco took hold, its four-on-the-floor pulse and long, hypnotic vamp sections nudged jazz-funk toward straighter, more dance-oriented forms, but without losing the syncopation or swing. The lush string charts and polished percussion of Philly soul began to seep into the CTI/Kudu sound, giving the genre its cinematic warmth.

In New York, Black FM radio and clubs like the Paradise Garage played jazz-funk alongside disco, building a shared audience. You can hear the connection in The Crusaders’ “Street Life,” George Benson’s late-’70s hits, Herbie Hancock’s “I Thought It Was You” (1978), Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” (1976) and “Running Away” (1977), or Lonnie Liston Smith’s “Expansions” (1975), all records that danced between genres.

Across the Atlantic, British musicians picked up the torch. Bands like Light of the World, Incognito, and Shakatak turned jazz-funk into a distinctly UK dance language. In Britain, it became more than a style, it became a social movement.

By the late ’70s, jazz-funk weekends were the sound of escape. In a country still marked by racism and economic tension, these scenes created rare spaces of inclusivity, where Black and white youth came together simply to dance. For many, those nights were a refuge, a place to step outside daily life and lose themselves in rhythm.

At the center of that groove,spiritually and musically, was Idris Muhammad.

His first album for Kudu Records

🎛️ After “Heaven”: What Happened Next?

After “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This,” Idris Muhammad kept recording, albums like Boogie to the Top carried his signature groove, but none quite reached the same transcendence. By the early 1980s, jazz-funk’s flame was fading in the U.S., eclipsed by hip hop and hi-NRG disco.

Muhammad drifted back toward jazz, reconnecting with artists like Ahmad Jamal, Johnny Griffin, and Pharoah Sanders, and grounding his playing once again in spiritual depth rather than chart ambition.

Yet his influence never disappeared. In the 1990s, DJs and collectors rediscovered “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”during the acid-jazz revival, and by the 2000s, it had become a sampling goldmine, a timeless groove reborn for new generations.

This is the title track from the follow up album of 1978. Same structure as “Heaven”

🎧 Sampled by the Future

“Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” has been sampled and reworked by a long list of artists. Drake flipped it on Comeback Season, and Jamiroquai nodded to it on “Alright.” In the early-2000s nu-disco moment, its DNA surfaced in big club cuts like “Rise” (The Soul Providers) and “Higher & Higher” (Milk & Sugar). It’s also been re-edited endlessly, by Danny Krivit, Joey Negro (Dave Lee), and Dimitri From Paris, proof that this groove doesn’t age.

🪩 The Legacy: A Groove That Transcends Categories

Idris Muhammad taught us that genres are just containers. What mattered to him was feel, that sense that every beat could lift your soul a little higher. “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This” wasn’t trying to be disco or jazz; it was reaching for transcendence.

He would later answer, when asked what style he was playing:

For anyone tracing the history of dance music between 1975 and 1995, this track is a perfect example of how the spiritual side of jazz flowed into the hedonism of disco, and how both eventually gave rise to house, acid jazz, and everything that followed.

If Idris Muhammad is new to you, start with the album Turn This Mutha Out, and let that groove do the talking.

💬 Your Turn

Where were you the first time you heard Could Heaven Ever Be Like This? Was it on a dancefloor, a mixtape, or a sample buried inside something else? Or is this the first time you get to hear it? And how do you like it?

👉 Leave a comment below and help me build the community by sharing the newsletter

Further reading (or should I say watching)

There are a number of interesting video’s/links :

(Sadly, there aren’t any 😃. This is the first week I haven’t been able to find a single video of Idris performing, not even a Soul Train clip with the dancers. The CTI promo machine just never reached that far.)

So You Wanna Hear More ?

I thought you would !

It’s fun to write about music but let’s be honest. Music is made to listen to.

Every week, together with this newsletter, I release a 1 hour beatmix on Mixcloud and Soundcloud. I start with the discussed twelve inch and follow up with 10/15 songs from the same timeframe/genre. The ideal soundtrack for…. Well whatever you like to do when you listen to dance music.

Listen to the Soundtrack of this week’s post on MIXCLOUD

Or on Youtube :

So what’s in this week’s mix ?

I always let the music lead the way, and this week it pulled me in a surprising direction. There’s a strong Eurodisco current running through the set, alongside some pure 1977 funk-driven disco gems like T-Connection’s “Do What You Wanna Do”, The Hues Corporation’s “I Caught Your Act”, and Carol Douglas’ “Burnin’.”

We kick things off with Idris Muhammad’s incredible “Could Heaven Ever Be Like This”, seamlessly blending into Don Ray’s “Got to Have Loving.” Don Ray might be the closest Eurodisco ever came to the American jazz-funk sound of that era, lush, rhythmic, and full of groove. It probably has to do with the fact that Don Ray’s song was created by Cerrone, who started his career as a drummer.

There are some deep cuts too, like The Southroad Connection’s “You Like It, We Love It” (we sure do 😁) and a real surprise: Carole King, yes, that Carole King, with her disco track “Disco Tech.”

And because 1977 was also the year of the great disco symphonies, I couldn’t resist including a pair of epic album-side journeys: Alec R. Costandinos’ “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” and Ferrara’s “The Wuthering Heights Suite.”(Don’t worry, it has nothing to do with Kate Bush’s hit a few years later 😂)

Enjoy the ride! 🎶

Next week, we’ll move into what was arguably the golden age of the twelve-inch, the 1980s, when it became the dominant format for singles. By then, almost every release, even ballads and rock tracks, came with its own extended version.

Our way in? A song by a short-lived ’80s band formed by two of the finest songwriters of their generation, one American, one British. An episode where I’ll be collaborating with the one and only

it all comes together....

A great story about Idris, thanks for this Pe. I immediately checked out "allright" by Jamiroquai to spot the sample of "Could heaven ever be like this".

Fun fact, November 25 I will go to Jamiroquai's concert in the Ziggo Dome Amsterdam. He kicked off his world tour two days ago in Barcelona. This show started with a DJ support set from Cerrone.

Now I am connecting all the dots😁

Another good one sparking the convo...