Casablanca Records: Neil Bogart Before the Label (the groundwork for disco’s biggest story) Part 1

The Twelve Inch 001 : The Story Of Casablanca Records Part 1

Welcome to the first post in the “second layer” of this newsletter on the history of dance music. As I explained in episode 100, this layer ties things together. These pieces won’t run in strict order. They’ll dig into questions, labels, periods, people.. etc... Think of them as the tissue between the weekly stories, a bigger, living book.

We’ll start with Casablanca Records and its founder, Neil Bogart. Casablanca is often held up as the epitome of what was “wrong” with disco, a view shaped by the sensational chapter in Fredric Dannen’s Hit Men (late 1990s). I want to tell a more balanced story. Neil Bogart and Casablanca mattered to the disco boom and how it evolved. But disco wasn’t an island. It didn’t appear out of nowhere. It grew from what was happening in society and in the music business.

In these first posts of the second layer, I’ll zoom in on specific parts of disco. You can expect me to tackle some 80’s subjects in 2026. Most subjects will run over several posts. I’ll publish weekly. They won’t follow a fixed timeline; they’ll land when they’re ready.

A note on access: most of this will be paywalled. It’s research-heavy, and I take that work seriously, as you know by now. If you can and you enjoy the project, please consider a paid subscription to support this community.

Now, on with the show, starting with a personal story to set the scene.

This is The Twelve Inch, my newsletter about the history of dance music from 1975 to 1995.

If this landed in your inbox because a friend forwarded it, I’d love for you to subscribe so you don’t miss the weekly episodes. Each one dives into a track, its story, and the culture around it.

And if you’re already enjoying the free posts, would you consider becoming a paid subscriber? Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and unearthing the stories behind the music.

💿 From Antwerp Record Racks to Superclub Chaos

I began my career in music retail in Belgium. Back then, the landscape was very different. Independent shops existed, but the big multi-store chains ruled the market. The pay wasn’t great, but if you wanted to break into the music industry, retail was the usual first step.

I ran one of the larger stores in Antwerp. It was the peak CD era, no streaming, no peer-to-peer yet. If you wanted music, you bought it on disc. We sold mountains of them.

When the chain’s head buyer left for a record company (the career move everyone dreamed of), I applied for the job but didn’t get it. So I jumped to the number two retailer, SuperClub. That’s where things turned surreal

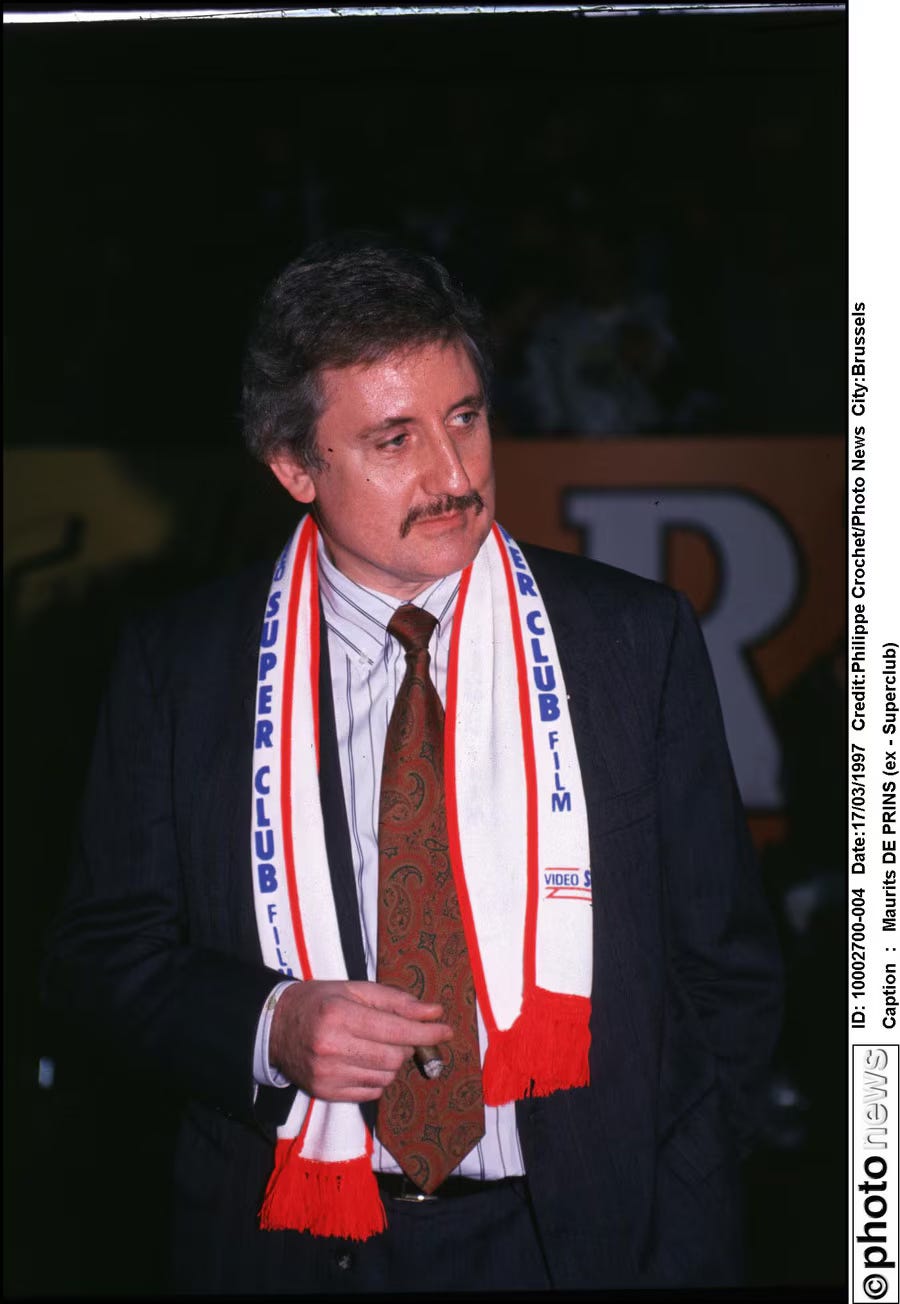

Maurits De Prins, founder of the Super Club imperium. In many senses the Belgian retail equivalent of Neil Bogaert

SuperClub, started in 1983 by a snackbar owner (Maurits De Prins), grew at lightning speed. At its height it ran hundreds of video and music stores in the Benelux, nearly 500 in the US, and had big expansion plans across Europe.

Philips was one of its investors. By 1992, the electronics giant had taken control, hoping to tie retail directly to its hardware business. It wasn’t just Philips, many consumer-electronics firms thought they needed their own retail arms. Almost all of those adventures ended badly. SuperClub was no exception.

By the late ’90s, the stores shut down. They had never turned a profit and were caught up in scandals, forgery, and embezzlement. I finished there as head buyer.

The losses were easy to explain: the company wasn’t organized. I ordered huge shipments of big new releases, only to see them vanish into thin air in the stores. Stock tracking was as unreliable as a fortune teller. Albums disappeared when demand was high and reappeared when the moment had passed.

Like Casablanca, Super Club also had ambitious plans for its headquarters. The original idea was to build a glass pyramid shaped like the logo, but in the end they chose a more conventional design. The photo only shows the first building, there were actually four more like it, plus a large warehouse. At most, two of them were ever partially occupied; the rest stood unused.

If you remember the KISS story (see episode 180) and the flood of solo albums in 1978, you’ll recognize the pattern. In many ways, SuperClub was the retail equivalent of Casablanca Records: fast rise, faster fall, and management like steering a container ship through heavy fog. You knew you’d end up somewhere, but was it the right place? And what damage would you cause along the way? In both cases, Philips ended up footing the bill: directly at SuperClub, indirectly through PolyGram at Casablanca.

Both stories show how overreach ends in tears. But there’s one difference: SuperClub never had the rock’n’roll edge that Casablanca carried in the late ’70s.😁

Of course they had to sponsor a soccer team, jerseys with the Super Club logo.

Today, I want to tell you that story. Casablanca Records, and Neil Bogart who drove it, created more than hit records and notorious parties. It’s a story of ambition, excess, and innovation, and what happens when a label bets everything on one genre. Because of its role in disco, it also became a kind of petri dish of the movement itself.

This will be a four-part series. Part 1 looks at Neil Bogart’s story before Casablanca. In part 2 I’l tell the story of Casablanca Records from its origins to it’s demise. Parts 3 and 4 will take on the bigger questions:

How did Casablanca rise to be the premier disco label?

Why did PolyGram buy it?

What innovations did it really bring?

Could it have survived?

So, camels ready? Let’s head to Casablanca.

Welcome, I’m Pe Dupre and I’m really glad you’re here. This is “The Twelve Inch”, my newsletter that tells the history of dance music between 1975 and 1995, one twelve inch at a time.

If you’ve received this newsletter, then you either subscribed or someone forwarded it to you. If you fit into the latter and want to subscribe, please do so. That way you will not miss any of my weekly episodes.

👶 Brooklyn Roots: How a Hustler Is Made

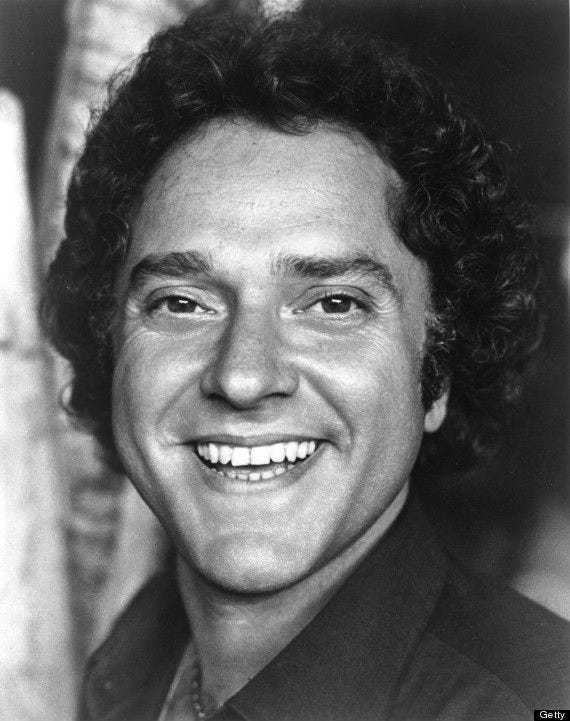

The story of Casablanca Records is also the story of its founder, Neil Bogart. His path was unusual. The music industry has always had hustlers, but few could claim they shaped not one but two major genres.

Neil was born Neil Bogatz in Brooklyn in 1943, the same year the film Casablanca won the Oscar for Best Picture. He and his sister Bonnie grew up with a creative but shy father, Al, who wrote music, and a strict, demanding mother, Ruth. Ruth pushed her children hard, failure wasn’t an option. To avoid punishment, they had to meet her expectations.

Still, both parents loved culture and music, and that passion rubbed off on their kids. Neil set his sights on show business. His first shot came when he recorded “Bobby” under the name Neil Scott. It reached No. 58 on the Billboard Hot 100, but his career stalled. His grandmother’s verdict was sharp: “A has been who never was.” Neil learned early that the industry could chew you up and spit you out.

☎️ The Cashbox Gambit

With no career momentum, he took a job at a talent agency. But music kept calling. When he spotted an opening at the industry magazine Cashbox, he faked a reference call under another name, recommending “the perfect candidate: Neil Bogart.” After enough follow-ups, the trick worked, he got the job. It was an early masterclass in self-promotion.

🧩 Sales, A&R, and the Hook

From Cashbox he moved to MGM as a promo manager, then to Cameo-Parkway Records to head sales. There he signed ? and the Mysterians, who hit No. 1 with “96 Tears.” He showed a knack for spotting hooks, the moments that grab a listener. His promo work paid off, and he became VP.

But it was at Buddah Records, starting in 1967, where Neil really made his mark. At just 24, he became its first president. While most of the music world was leaning into politics, rebellion, and drugs, Neil went the other way. He created fun, lighthearted songs built around catchy hooks, what became known as bubblegum pop.

🍬 The Bubblegum Playbook at Buddah

Bubblegum Pop was rock’n’roll stripped of anger and edge. Who played or sang didn’t matter; the songs were interchangeable. Producers Jerry Kasenetz and Jeff Katz churned out hits like the 1910 Fruitgum Company and Ohio Express’s “Yummy Yummy.”

Neil knew the game wasn’t about writing or singing, it was about making sure the right people heard the record at the right time. His mantra was simple: do “whatever it takes.” Budgets were meant to be spent, not saved. Careful promo managers had no place at Buddah, or later, Casablanca.

The bubblegum years gave Neil tools he would use again: theatricality, camp, and unforgettable choruses. Those same elements would later shape the Village People and the marketing of disco itself.

“I don’t sell records. I sell dreams.” : Neil Bogart (quoted in Larry Harris’ And Party Every Day: The Inside Story of Casablanca Records)

🧭 What Comes Next

Next week, we launch Casablanca: the Warner deal, the KISS slog, near-failure, then the run that changed pop.

🗣️ Your turn

What’s your earliest memory of bubblegum pop crossing into your world, on radio, jukebox, or TV? Drop a note below.

Fantastic start to the series. I'm already learning so much! I knew nothing about Neil Bogart, and only tangentially about Casablanca Records, so this is proving very educational.

I guess my first memory of bubblegum pop has got to be either Aqua or the Spice Girls 🤩

Now, talking about bubblegum or rather teen pop... this came out a bit later than Aqua and the SG. It was a megahit in Argentina and, I suspect, in the rest of the Spanish-speaking world as well. She might have been your neighbour. Can you hazard a guess before you click on the link? 😂 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eZyU6H3NcT8&list=RDeZyU6H3NcT8&start_radio=1

Taking time on these history articles. Of course I met and interviewed FD re: Hit Men and got a signed copy.

It was for an article entitled "RICO IN THE ENTERTAINMENT BUSINESS" I wrote while in Law School for the NY Law Journal's ENTERTAINMENT LAW & FINANCE. I interned there and was a stringer after I became a lawyer. Cited in LA's Loyola Law School Law Review one of my first legit published articles.

The crux is that the music business is particularly corrupt top to bottom but we like it, like it, yes we dooooo...

Writing about it is a good deed doing something about it... impossible. The Spotify expose Mood Machine by Liz Pelly is the latest attempt but always self-interest drives America. The biz is more consolidated than ever and a fair structure more elusive. My take is that rogue elements are better than corp criminals. But once you're dangling over the balcony you'll agree to play ball or you'll become a lawyer. At least now I still have a career. Singing like a bird I still get gigs. We are the meat that gets dangled in front of the lions who still run the show as the apex predators. Just look at how many climbed all the way up the hill and crashed landed including Neil Bogart.

Always a provoking disco-tion!