🎶 Before Saturday Night Fever: How Tavares Mastered Disco, and Missed Its Big Moment

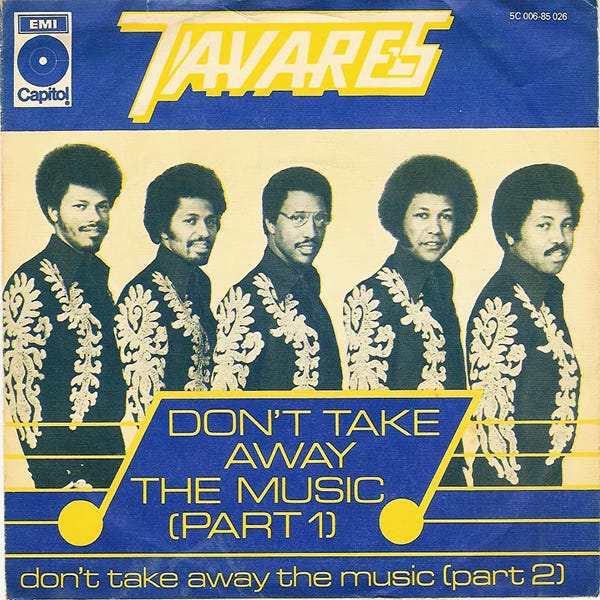

The Twelve Inch 196 : Don't Take Away The Music (Tavares)

Let’s start with a bit of housekeeping. As announced last week, from this week on I’ll be including a read-aloud version of my weekly Substack. Give me a few weeks to get the hang of it — it’s fun, but also a bit more of an uphill battle than I expected (which, to be fair, is not uncommon for me 😁).

Accent and mispronunciations aside (I’m well aware of those), I’d really appreciate any feedback if you give this first one a try.